Abstract

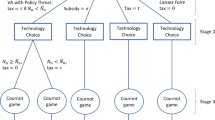

Several product-related voluntary agreements (VAs) have emerged between firms to limit production of energy-consuming products, e.g., domestic appliances and automobiles. While some VAs have been successful in achieving their targets, others have failed. The paper identifies two factors that can explain the success or failure of product-related VAs. The first is a technological property of the product line: whether provision of energy-efficient products requires a quality compromise (quality–efficiency trade-off). The second is the type of the constraint imposed by the VA: a quota on the brown model or a VA based on an average efficiency standard. I show that VAs are more likely to be successful for products where there is no quality–efficiency trade-off than for products where there is such a trade-off. I also show that quantity-based VAs are more likely to emerge than VAs imposing an average efficiency standard. The findings provide a possible explanation for why the CECED appliances VAs have been successful in achieving the targets they set, while the ACEA agreement for automobiles has failed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles and news from researchers in related subjects, suggested using machine learning.Notes

The quality–efficiency trade-off can be interpreted as the short run situation where firms only have access to technologies that allow production of green products by sacrificing other product qualities. In the long run technological innovation in product design may enable firms to modify their product lines so as to produce green products without deterioration in other product quality attributes.

According to Ward’s Automotive Yearbook (2009), small cars have higher miles per gallon than luxury cars; however, they are smaller in size and have a weaker horsepower than luxury cars. Also, the price of small cars is less than the price of luxury cars. This suggests that consumers value inefficient cars more than they value efficient cars, assuming a vertically differentiated product market.

According to Consumer Reports (2011), front-loading washing machines rank higher than top-loading machines in terms of energy and water efficiency. While the cycle time of front-loading machines is longer, their overall ranking is still higher than the overall ranking of top loading machines, where overall ranking is based on washing performance, gentleness, noise energy efficiency, water efficiency and cycle time.

Ahmed and Segerson (2011) only consider a quota-based VA applied to products that do not exhibit a quality–efficiency trade-off. It analyzes participation incentives and highlights the need of an enforcement device to ensure sufficient participation. This paper focuses instead on contexts where VAs are likely to be profitable by considering the role of the standard implemented by the VA as well as the trade-off between product quality and efficiency.

Alternatively, not buying a new model may mean that those consumers are holding onto their old model. This will not significantly affect our results, except that (14) would be interpreted as energy consumption from new models only.

This is consistent with the empirical literature, which suggests that while the more efficient (green) models are typically used more frequently, a phenomenon referred to as the rebound effect, the total energy consumed by the energy-efficient model is less (see for example Small and Van Dender 2006).

Although I simplify and assume that both β s and L s are exogenous, they can both depend on the frequency of use of each model. This specification will not change the results of the paper since the frequency of use depends on exogenous product characteristics (e.g., energy efficiency and quality) and energy price which is held constant.

The model is an extension to Ahmed and Segerson (2011) where I model two product attributes that consumers value, energy efficiency and product quality, instead of energy efficiency only.

Proofs of all propositions are provided in the Appendix (Online Resource 1).

Enforcement can be achieved if information about participation is made public and firms care about their image, by the use of trigger strategies in repeated interactions, or by using a regulatory threat. For a discussion of a firm’s incentive to free ride, the impact of free riding and possible enforcement mechanisms, see Ahmed and Segerson (2011).

The average efficiency standard is usually specified as a limit on the average of energy efficiency (energy consumed per use) across the models rather than the average of lifetime energy consumed. For example, the ACEA agreement sets a limit on the average CO2 emissions per kilometer driven. However, since the green model uses less energy per use and less in total, both specifications simplify to a limit on the ratio of the brown to the green model as shown in the paper.

A mild average efficiency standard can increase consumer surplus under the trade-off market. This is because the gain to consumers from the reduction in the price of the green model outweighs the loss from the increase in the price of the brown model. Note that for the no trade-off market, the consumer surplus always declines regardless of the standard used. Similarly, consumer surplus always declines under the quota regardless of the type of market. The changes in prices under these different cases will be explained in the following sections.

See proof of Proposition 2 for a detailed explanation.

Derivation of the iso-profit line is shown in the Appendix (Online Resource 1).

This is an application of the general principle that, in the presence of strategic behavior, the shadow price of a constraint is not the Lagrange multiplier (see Caputo 2007).

The effects of the agreements on output and prices in a market with n firms are qualitatively the same as for the monopoly market. However, the impact on profit is different. The VA always leads to a decline in monopoly profit.

The sign of the strategic effect is generally ambiguous. The constraint can increase or decrease competition depending on the specific demand functions as well as the type and stringency of the restriction imposed on firms.

If \( \frac{{{\text{d}}Q_{\text{G}}^{TZ} }}{{{\text{d}}Q_{\text{B}}^{TZ} }} > - \frac{{L_{\text{B}} }}{{L_{\text{G}} }}, \) then energy consumption decreases with a decline in Z.

The impact on social welfare is beyond the scope of analysis of this paper where the main concern is the profitability of the VA and its impact on energy consumption. However, it can be shown that a mild standard under the trade-off market increases the sum of consumers and producers surplus, as it expands production in an imperfectly competitive market. Its impact on social welfare will depend on how the VA affects energy consumption and on the stringency of the standard.

In Fischer (2005), the imposition of an average efficiency standard always reduces firm profit in contrast to the results in this paper. That is because she considers a monopoly market and the standard restricts the monopolist’s choices or reduces his ability to extract surplus from consumers. However, this paper shows that in a market with n firms, it is possible that the standard reduces competition between firms and thus results in a higher firm profit.

This is the type of constraint used in the European washing machine agreement. The agreement also had a target for average energy efficiency, but given the commitment to eliminate production and sales of low-efficiency machines, the average efficiency target was not binding.

The maximization problem under the average efficiency standard can also be written such that q iB is the only choice variable, since \( q_{\text{G}}^{i} = \frac{{q_{\text{B}}^{i} }}{Z} \). However, the fact that q iG is a function of q iB under the average efficiency standard, which is not true under the quota, makes the two problems totally different since the choice of q iB directly affects the output of the other model.

Even though a profitable agreement exists, in the absence of an enforcement device, it is not a Nash equilibrium, i.e., in the absence of the agreement, both firms would choose not to limit production of the brown model on their own and hence the agreement constitutes a binding restriction on their choices.

This can explain why the European Committee of Domestic Equipment Manufacturers has decided in April 2007 not to update their VAs on product energy efficiency (CECED 2007). While enforcement problems could be a possible reason behind not updating the VAs as the CECED claims, it is also possible that the agreement has limited production of the inefficient model, such that further reductions would reduce industry profit as explained in Proposition 5.

The quota-based VA always reduces the sum of consumer and producer surplus as it exacerbates the underproduction problem. Whether it raises social welfare or not will depend on the magnitude of environmental damages from energy consumption.

References

Ahmed R, Segerson K (2011) Collective voluntary agreements to eliminate polluting products. Resour Energy Econ 33:572–588

Alberini A, Segerson K (2002) Assessing voluntary programs to improve environmental quality. Environ Resour Econ 22:157–184

Arora S, Gangopadhyay S (1995) Toward a theoretical model of voluntary overcompliance. J Econ Behav Organ 28:289–309

Blackman A, Darley S, Lyon TP, Wernstedt K (2010) What drives participation in state voluntary cleanup programs? Evidence from Oregon. Land Econ 86:785–799

Brander JA, Eaton J (1984) Product line rivalry. Am Econ Rev 74:323–334

Caputo M (2007) The Lagrange multiplier is not the shadow value of the limiting resource in the presence of strategically interacting agents. Econ Bull 3:1–8

CECED (2002) Second voluntary commitment on reducing energy consumption of domestic washing machines (2002–2008). Presented to the European Communities Commission and the European Parliament

CECED (2003) CECED Voluntary commitment II on reducing energy consumption of household washing machines. In: 1st Annual report to the European Communities Commission

CECED (2004) Summary of CECED unilateral industrial commitments. CECED Publication

CECED (2007) Top executives discontinue voluntary energy efficiency agreements for large appliances. CECED Press Release, 21 March

Champsaur P, Rochet JC (1989) Multiproduct duopolists. Econometrica 57:533–557

Chen C (2001) Design for the environment: a quality-based model for green product development. Manag Sci 47:250–263

Commission Staff (2009) Regulation (EC) No 443/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 April 2009. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:32009R0443:EN:NOT

Confederation of European Paper Industries (2000) The European Declaration on Paper Recovery. http://www.paperrecovery.org/files/English-164625A.pdf

Consumer Reports (2011) Washing machines: ratings. January

Crandall RW (1992) Policy watch: corporate average fuel economy standards. J Econ Perspect 6:171–180

Dawson NL, Segerson K (2008) Voluntary agreements with industries: participation incentives with industry-wide targets. Land Econ 84:97–114

De Fraja G (1996) Product line competition in vertically differentiated markets. Int J Ind Organ 14:389–414

European Recovered Paper Council (2002) The European Declaration on Paper Recovery Annual Report 2002. http://www.paperrecovery.org/files/ERPC%20AR%202002%203-093429A.pdf

Fischer C (2005) On the importance of the supply side in demand side management. Energy Econ 29:83–101

Fleckinger P, Glachant M (2010) Negotiating a voluntary agreement when firms self-regulate. Université Paris1 Panthéon-Sorbonne (post-print and working papers) hal-00529632_v1, HAL

Glachant M (2007) Non-binding voluntary agreements. Post-Print hal-00437769_v1, HAL

Heretier A, Eckert S (2009) Self-regulation by associations: collective action problems in European environmental regulation. Bus Polit 11:Art. 3

Johnson JP, Myatt DP (2003) Multiproduct quality competition: fighting brands and product line pruning. Am Econ Rev 93:748–774

Khanna M (2001) Non-mandatory approaches to environmental protection. J Econ Surv 15:291–324

Lyon TP, Maxwell JW (2001) Voluntary approaches to environmental regulation: a survey. In: Franzini M, Nicita A (eds) Economic institutions and environmental policy. Ashgate Publishing, Aldershot

Lyon TP, Maxwell JW (2003) Self-regulation, taxation and public voluntary environmental agreements. J Public Econ 87:1453–1486

Oikonomou V, Patel MK, Gaast WV, Rietbergen M (2009) Voluntary agreements with white certificates for energy efficiency improvement as a hybrid policy instrument. Energy Policy 37:1970–1982

Onoda T (2008) Review of international policies for vehicle fuel efficiency. International Energy Agency Information Paper. http://www.iea.org/papers/2008/Vehicle_Fuel.pdf

Schnabl G (2005) The evolution of environmental agreements at the level of the European Union. The handbook of environmental voluntary agreements; design, implementation and evaluation issues. Springer, The Netherlands, pp 93–106

Segerson K, Li N (1999) Voluntary approaches to environmental protection. In: Folmer H, Tietenberg T (eds) The international yearbook of environmental and resource economics 1999/2000. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

Segerson K, Miceli TJ (1998) Voluntary agreements: good or bad news for environmental protection? J Environ Econ Manag 36:109–130

Segerson K, Wu J (2006) Nonpoint pollution control: inducing first-best outcomes through the use of threats. J Environ Econ Manag 51:165–184

Small KA, Van Dender K (2006) Fuel efficiency and motor vehicle travel: the declining rebound effect. Energy J 28:25–52

Videras J, Alberini A (2000) The appeal of voluntary environmental programs: which firms participate and why? Contemp Econ Policy 18:449–460

Ward’s Automotive Yearbook (2009) Ward’s ‘09 light vehicle US market segmentation and prices, pp 256–257

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Shunsuke Managi, the journal co-editor, and to two anonymous referees for their comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmed, R. Promoting energy-efficient products: voluntary or regulatory approaches?. Environ Econ Policy Stud 14, 303–321 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10018-012-0032-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10018-012-0032-8