Abstract

The paper constructs an asymmetric information model to investigate the efficiency and equity cases for government mandated benefits. A mandate can improve workers’ insurance, and may also redistribute in favour of more ‘deserving’ workers. The risk is that it may also reduce output. The more diverse are free market contracts—separating the various worker types—the more likely it is that such output effects will on balance serve to reduce welfare. It is shown that adverse effects can be reduced by restricting mandates to larger firms. An alternative to a mandate is direct government provision. We demonstrate that direct government provision has the advantage over mandates of preserving separations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

A similar fall in labour productivity, although not on this occasion arising from the asymmetric information mechanism, obtains in the model of Hopenhayn and Rogerson (1993).

The OECD (1995, p. 190) surveys parental leave in 19 countries, and states that the absence of a key worker for a long period created difficulties for small firms. This explains the exemption, for example, of firms employing less than 50 workers from the provisions of the 1993 US Family and Medical Leave Act.

The Lagrangean is

$$ P_{{\text{H}}} U_{{\text{F}}} {\left( b \right)} + {\left( {1 - P_{{\text{H}}} } \right)}U_{{\text{S}}} {\left( w \right)} + \lambda {\left[ {P_{{\text{H}}} {\left( {F - b} \right)} + {\left( {1 - P_{{\text{H}}} } \right)}{\left( {S - w} \right)}} \right]}. $$Differentiating with respect to b and w and equating to zero,

$$P_{{\text{H}}} U^{\prime } _{{\text{F}}} {\left( b \right)} = \lambda P_{{\text{H}}} $$$${\left( {1 - P_{{\text{H}}} } \right)}U^{\prime } _{{\text{S}}} {\left( w \right)} = \lambda {\left( {1 - P_{{\text{H}}} } \right)}.$$Equation 7a follows from these two equations. The constraint gives Eq. 7b.

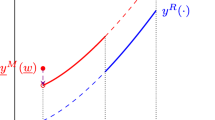

We can show that U L declines to the right of E L ′ on the line R L=0 (Fig. 1). From Eq. 8, since R L=0 has slope\( - Q_{{\text{L}}} = { - P_{{\text{L}}} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{ - P_{{\text{L}}} } {{\left( {1 - P_{{\text{L}}} } \right)}}}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {{\left( {1 - P_{{\text{L}}} } \right)}} \),

$${{\text{d}}U_{{\text{L}}} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{\text{d}}U_{{\text{L}}} } {{\text{d}}b}}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {{\text{d}}b} = P_{{\text{L}}} U^{\prime } _{{\text{F}}} + {\left( {1 - P_{{\text{L}}} } \right)}U^{\prime } _{{\text{S}}} {\left( {{{\text{d}}w} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{\text{d}}w} {{\text{d}}b}}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {{\text{d}}b}} \right)} = P_{{\text{L}}} {\left( {U^{\prime } _{{\text{F}}} - U^{\prime } _{{\text{S}}} } \right)}.$$As E L ′ lies on the full insurance line, we know that, to the right of E L ′, U F ′>U S ′. Thus, from the above equation, to the right of E L ′, dU L/db>0, and U L declines as benefits are reduced. U H likewise declines to the right of E L ′ on the line R L=0, and declines also to the right of E H on the line R H=0 (the proofs are similar).

An assumption here is that the high-risk type cannot obtain insurance outside the firm (cannot ‘top up’ with insurance), on terms that, starting from E L, allow the high-risk type to attain levels of utility higher than U H *.

An alternative approach that might be considered relies on the concept of a “potential” Pareto improvement. (A potential Pareto improvement occurs when ‘winners’ can compensate ‘losers’ and still come out ahead.) However, when applying this concept in our context, intransitivities arise. A in Fig. 1 is a potential Pareto improvement on (E H,E L), since redistribution is possible from A to (E H,E L ′) which itself is a Pareto improvement on (E H,E L). Thus A is ‘better’ than (E H,E L). On the other hand, redistribution is possible also from (E H,E L) back to A, so that (E H,E L) is no worse than A. A second problem with the concept of a potential Pareto improvement, in our context, is that winners compensating losers would in practice be impossible. When for example A is mandated, forcing pooling, low-risk types cannot be compensated by high-risk types, since the latter are not identifiable. Though a popular tool in many contexts, the concept of a potential Pareto improvement is not useful here.

Adapting Eqs. 5 and 8, the Lagrangean for the determination of E is

$$ P_{{\text{L}}} U_{{\text{F}}} {\left( {b + z} \right)} + {\left( {1 - P_{{\text{L}}} } \right)}U_{{\text{S}}} {\left( {w - Qz} \right)} + \lambda {\left[ {P{\left( {F - b} \right)} + {\left( {1 - P} \right)}{\left( {S - w} \right)}} \right]}. $$Differentiating with respect to b and w, and equating to zero, \(P_{{\text{L}}} U^{\prime } _{{\text{F}}} = \lambda P\) and \({\left( {1 - P_{{\text{L}}} } \right)}U^{\prime } _{{\text{S}}} = \lambda {\left( {1 - P} \right)}.\) Dividing gives Eq. 21a. The constraint gives Eq. 21b.

This Pareto improvement result is also derived heuristically by Wilson (1977, p. 200), although he errs in claiming that Pareto improvements can always be achieved. A similar effect occurs when a firm, which is able to offer more than one contract, uses a profit-making contract aimed at low-risk types to balance a loss-making contract designed for high-risk types. The advantage gained is that the subsidised high-risk types are less inclined to mimic the low-risk types (see Cave 1984, in the insurance market context).

References

Aghion P, Hermalin B (1990) Legal restrictions on private contracts can enhance efficiency. J Law Econ Organ 6(2):381–409

Blackorby C, Donaldson D, Weymark JA (1997) Aggregation and the expected utility hypothesis. Mimeograph, University of British Columbia

Cave J (1984) Equilibrium in insurance markets with asymmetric information and adverse selection. RAND Report R-3015-HHS

Cooper R, Hayes B (1987) Multi-period insurance contracts. Int J Ind Organ 5(2):211–231

Dionne G, Lasserre P (1987) Adverse selection and finite horizon insurance contracts. Eur Econ Rev 31(4):843–861

Encinosa W (1999) Regulating the HMO Market. Mimeograph, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, US Department of Health and Human Services

Harsanyi J (1977) Rational behaviour and bargaining equilibrium in games and social situations. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

Hellwig M (1987) Some recent developments in the theory of competition in markets with adverse selection. Eur Econ Rev 31(1–2):319–325

Hopenhayn H, Rogerson R (1993) Job turnover and policy evaluation: a general equilibrium analysis. Eur Econ Rev 101(5):915–938

Krueger AB (2000) From Bismarck to Maastricht: the march to the European Union and the labor compact. Labour Eco 7(2):117–134

Levine DI (1991) Just-cause employment policy in the presence of worker adverse selection. J Labor Econ 9(3):294–305

OECD (1995) Long term leave for parents in OECD countries, Employment Outlook 1995, pp. 171–202

Pattanaik PK (1994) Some non-welfaristic issues in welfare economics. In: Dutta, B (ed) Welfare Economics, Oxford University Press, London, UK, pp. 196–248

Rothschild M, Stiglitz JE (1976) Equilibrium in competitive insurance markets: an essay on the economics of imperfect information. Q J Econ 90(4):629–650

Ruhm CJ (1998) The economic consequences of parental leave mandates: lessons from Europe. Q J Econ 113(1):285–317

Stewart J (1994) The welfare implications of moral hazard and adverse selection in competitive insurance markets. Econ Inq 32(2):193–208

Summers LH (1989) Some simple economics of mandated benefits. Am Econ Rev 79(2):177–183

Wilson C (1977) A model of insurance markets with incomplete information. J Econ Theory 16(2):167–207

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank seminar participants at the University of Birmingham, the EIIW-Potsdam, the ZEW-Mannheim, and the EMRU workshop at Lancaster University. We retain responsibility for any errors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Addison, J.T., Barrett, R.C. & Siebert, W.S. Building blocks in the economics of mandates. Port. Econ. J. 5, 69–87 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10258-006-0009-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10258-006-0009-2