Abstract

Conservation contracts between a landholder and an agency are characterised by information asymmetries since monitoring is incomplete and the provided outcome is often not verifiable. This contractual relationship is complicated by environmental risk, e.g. climatic conditions, that are often observable for the landholder, only. It was tested whether environmental risk is detrimental to the establishment of a reciprocal payment-effort relationship in an experimental auction-market for a public good. In this market, auction winning sellers either reinvest their contract payment in a public good or behave opportunistically and exploit information rents. The data show that environmental risk increases opportunistic behaviour of some sellers and disturbs the formation of effective, reciprocal contract relationships between the contracting buyers and sellers. Buyers do no longer trust sellers, pay minimal payments and break up after negative shocks. Repeated interaction mitigates the influence of environmental risk by benefitting contract enforcement and increasing efficiency due to higher reinvestment shares of payments, although the effect is less strong than in a comparable environment without risk. These results suggest that in a variable environment competitive bidding might be a less suitable mechanism for allocating conservation funds.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles and news from researchers in related subjects, suggested using machine learning.Notes

Total number of periods was not known to the subjects to avoid end-game effects.

Effort cost are calculated as follows \(c(e) =25\cdot 4^{(0.5+e/100)}\), e is defined within the interval (0, 100).

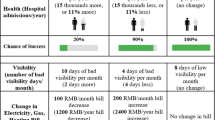

The individual share of the contract dividend d is calculated according to \(d= mv (0.5+e/100)/n\), where m is 0.5, 1.0 or 1.5 (\(p=0.33\)), \(v\) is a level parameter (set to 551), e is effort in the interval of (0, 100) and n is the number of market participants (4).

The individual optimum transforms to a range of optimal values within the effort domain [75, 85] in the experiment, resulting from rounding of values and the technical implementation of a slider that does not allow precise entry of values.

The effort decision screen included a calculator showing the effort cost, contract dividend and individual profits.

227 out of 965 contracts were cases with contract dividends at the lower or upper part of the total spectrum. Contract dividends \(<\)69 indicated a downward transformation (70 contracts); contract dividends \(>\)207 indicated an upward transformation (157 contracts).

Instructions in BRID and BFID treatments did not include any information on a potential multiplier (See supplementary material).

Including a show-up fee of 2.50 € and the results of a standard lottery game, data not shown.

Wilcoxon signed rank tests indicated a significant difference between BFID and MFID (\(\hbox {z}=2.368\), \(p=0.018\)) and between BFID and BRID (\(\hbox {z}=6.792\), \(p<0.001\)).

Sellers in the MRID treatment reinvested on average only 75 % of their wages, sellers in the MFID treatment spent 83 % on the public good. By contrast, sellers in the base market with fixed identities and partner matching kept only 10 % of their wages to themselves. This share rises to 21 % in the random base market, confirming increased opportunism in an anonymous market context.

The estimates are based on the following empirical model:

Fig. 3 Distribution of effort choices in periods with negative, neutral and positive shocks, and corresponding BASE markets. Note: Box-whisker plots with median, 25 and 75 percentile ranges and outliers. The vertical bars indicate minimum and maximum (excluding outliers). a Negative shock (\(m=0.5\)). b Neutral shock (\(m=1.0\)). c Positive shock (\(m=1.5\)). d Baseline (\(m=1.0\))

\({ EFFORT}= \alpha + \beta _1 { OFFER}+ \beta _2 { OFFER}^{2}+\gamma _1 { FID} + \gamma _2 { NEG} + \gamma _3 { POS} + \gamma _4 { FID}\times { NEG}+ \gamma _5 { FID}\times { POS}+{ error}\).

Coefficients presented must be interpreted with regard to the base category (MRID with neutral shock). In view of a neutral shock (\(\hbox {m}=1.0\)), RISK markets resembled BASE markets (cf. Fig. 3), with efforts in the MFID treatment exceeding MRID performance significantly (Wilcoxon signed-rank test: \(\hbox {z}=2.775\), \(p=0.006\)).

The odds in favour of being accepted as a contractor are defined by the ratio of the probability of being accepted (p) to not being accepted (\(1-p\)). For example, in a market with three sellers (\(p=0.33\)), the odds for a seller to be chosen were 1:2. In a logit regression with standard output, the influence of an explanatory variable measured in odds is obtained by raising e to the power of the coefficient. Hence, a negative coefficient produces an odds ratio of a fraction smaller 1, a positive sign yields an odds ratio larger 1, and a coefficient of zero equals an odds ratio of one.

References

Arnold MA, Duke JM, Messer KD (2013) Adverse selection in reverse auctions for ecosystem services. Land Econ 89(3):387–412

Brown M, Falk A, Fehr E (2004) Relational contracts and the nature of market interactions. Econometrica 72(3):747–780

Brown M, Falk A, Fehr E (2012) Competition and relational contracts—the role of unemployment as a disciplinary device. J Eur Econ Assoc 10(4):887–907

Cason T, Gangadharan L (2005) A laboratory comparison of uniform and discriminative price auctions for reducing non-point source pollution. Land Econ 81(1):51–70

Cardenas JC (2011) Social norms and behavior in the local commons as seen through the lens of field experiments. Environ Resour Econ 48(3):451–485

Croson RT (1996) Information in ultimatum games: an experimental study. J Econ Behav Organ 30:197–212

Derissen S, Quaas MF (2013) Combining performance-based and action-based payments to provide environmental goods under uncertainty. Ecol Econ 85:77–84

Dickinson DL (1998) The voluntary contributions mechanism with uncertain group payoffs. J Econ Behav Organ 35(4):517–533

Fehr E, Brown M, Zehnder C (2009) On reputation: a microfoundation of contract enforcement and price rigidity. Econ J 119:333–353

Fehr E, Gächter S, Kirchsteiger G (1997) Reciprocity as a contract enforcing device: experimental evidence. Econometrica 65(4):833–860

Fischbacher U (2007) z-Tree—Zurich toolbox for readymade economic experiments. Experimenter’s manual. Exp Econ 10:171–178

Gangadharan L, Nemes V (2009) Experimental analysis of risk and uncertainty in provisioning private and public goods. Econ Inq 47(1):146–164

Gerhards L, Heinz M (2013) In good times and bad—reciprocal behavior at the workplace in times of economic crises. Goethe-University, Frankfurt. http://user.uni-frankfurt.de/~matthein/Dateien/CrisisPaper.pdf

Greiner B (2004) The online recruitment system ORSEE—a guide for the organization of experiments in economics, papers on strategic interaction 2003–10. Max Planck Institute of Economics, Strategic Interaction Group

Keser C, Montmarquette C (2008) Voluntary contributions to reduce expected public losses. J Econ Behav Organ 66:477–491

Linardi S, Camerer C (2012) Can relational contracts survive stochastic interruptions? Experimental evidence. California Institute of Technology Social Science Working Paper #1340. California Institute of Technology Working Paper. http://www.linardi.gspia.pitt.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/RelationalContracting_CamererLinardi.pdf

McAllister RRJ, Tisdell JG, Reeson AF, Gordon IJ (2011) Economic behaviour in the face of resource variability and uncertainty. Ecol Soc 16(3):6

Messick DM, Allison ST, Samuelson CD (1988) Framing and communication effects on group members’ responses to environmental and social uncertainty. Appl Behav Econ II:677–700

Rapoport A, Sundali JA, Seale DA (1996) Ultimatums in two-person bargaining with one-sided uncertainty: demand games. J Econ Behav Organ 30:173–196

Vogt N, Reeson AF, Bizer K (2013) Talking to the sellers: communication, competition and social gift-exchange in an auction for public good provision. Ecol Econ 93:11–19

Zabel A, Roe B (2009) Optimal design of pro-conservation incentives. Ecol Econ 69(1):126–134

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The author was research assistant at the Department of Economics, Georg-August University, Goettingen, Germany, and would like to thank Andrew Reeson and Kilian Bizer for helpful comments on this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vogt, N. Environmental Risk Negatively Impacts Trust and Reciprocity in Conservation Contracts: Evidence from a Laboratory Experiment. Environ Resource Econ 62, 417–431 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-014-9822-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-014-9822-8

Keywords

- Auctions

- Conservation tenders

- Conservation contracts

- Laboratory experiments

- Environmental risk

- Trust

- Reciprocity