Abstract

Using official statistics and tax laws, we outline and discuss the evolution of the personal income tax in Austria since the beginning of the Second Republic in 1955. Focusing on the tax tariff and its progressivity properties, we identify a period of high (and increasing) progressivity before 1989, followed by a period of diminished progressivity since 1989. While still being a powerful revenue instrument, the Austrian income tax seems to have lost both redistributive impact and political allure.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

This paper outlines and discusses the evolution of the personal income tax tariff in the Republic of Austria since the beginning of the Second Republic in 1955, when the country gained full independence after World War II. Relying on tax laws and statistics, we describe more than fifty years of tax rates, tax revenues, and tax burden distribution. To our knowledge, this study is the first one to look into the long-term trends of income taxation in Austria after the paper by Lehner (1981), who investigated the development of the Austrian income tax tariff between 1957 and 1983, and the study by Neill (1985), who explored the erosion of the Austrian wage tax between the mid-1960s and the mid-1980s. Former studies usually are confined to the short-term effects of single tax reforms on average and marginal tax rates as well as on progressivity (e.g., Breuss et al. 2004; Genser 1986; Lehner 1973, 1975, 1988; Lehner et al. 1993); and they do not attempt at a systematic comparison of income tax rates and of tax progressivity for different income groups in a long-term perspective. The paper concentrates on the taxation of earnings from dependent labor, we will, however, complement this analysis by looking into the evolution of the overall income tax system.

Our review shows that the history of Austrian income taxation since 1955 can be split up into two periods: before 1989 and since 1989. At the risk of over-simplifying, these two periods might also be called the periods of, respectively, high and decreasing progressivity. From 1955 to 1989, marginal and average income tax rates were steadily increasing, leading to a substantial degree of tax progressivity, although with a complex and non-uniform pattern. The 1988 tax reform, which was designed by the first Grand Coalition in office since 1966 and entered into force in 1989, brought a significant drop in average and marginal tax rates for all income groups (for details see Lehner 1988). Since then, average and marginal tax rates have been fairly constant, and the tax system has become less progressive in the sense that the gaps between marginal and average tax rates have been narrowed. From the viewpoint of tax politics, the period until 1989 might be called an activist one—with a major income tax reform in every 3.5 years on average; whereas in the more quiet period since 1989 only two income tax reforms were enacted.Footnote 1 Thus, the income tax tariff as a discretionary policy instrument somewhat seems to have fallen from grace with the Austrian government (which does not preclude, however, that tinkering with the details of the tax code is still en vogue).

Government revenues out of the income tax have risen, both in absolute and relative terms, over the past 50 years. Even the 1989 tax cuts only caused a temporary dip of revenues (particularly from the wage tax—“Lohnsteuer”) from which fiscal coffers quickly recovered.

Our analysis mimics a similar analysis by Corneo (2005) for Germany. Corneo (2005) identifies three different stages of the income tax for Germany since 1958. In a first, so-called golden age of the income tax from 1958 to 1974 average tax rates and, thus, progressivity rapidly increased. So did tax revenue as a percentage of GDP. The second period from 1975 to 1985 marks a period of transition with a boom of tax expenditures accompanied by increasing average tax rates (until 1981) until, after 1982, a period of tax avoidance (growing tax rates but constant tax revenues) began. The period from 1986 to present is characterized by a soft rolling back of the income tax, with a substantial decrease in revenues and tax rates after 1999 and the degeneration of what was once thought to be a comprehensive income tax to a wage tax. The post-war history of the Austrian income tax does not follow such a rise-and-decline pattern. The Austrian income tax has on the contrary always been alive and (quite) well, at least in its fiscal fruitfulness.Footnote 2

This paper complements studies by the OECD on “Taxing Wages”, published in yearly intervals (see OECD 2008, for the most recent issue). These reports compare trends and figures on personal income taxes and social security contributions paid by employees and their employers in the OECD countries. They focus on the size of the labor tax wedge for different representative household types which differ by income level and household composition; whereas distributional aspects do not play a central role. Similar to the OCED, we determine marginal and average tax rates for income from employed labor, although not covering social security contributions. This sheds light on the allocative distortions which the Austrian income tax might potentially have on labor supply. Our paper adds to the OECD reports by analysing the local progressivity of labor income taxation for different–representative–income levels in a long-term perspective.

Our analysis will proceed in several steps. Before turning to the changes in the income tax tariff over time (Section 3), we will briefly review some more general and structural trends in the Austrian income tax system (Section 2). Section 4 scrutinizes the evolution of the progressivity of the Austrian income tax. Section 5 digresses to a brief analysis of the most recent income tax reform while Section 6 analyses the role of the income tax as a means to raise revenues. Section 7 concludes by attempting to provide some interpretations for the long-term developments observed.

2 Structural changes in the Austrian income tax system since 1955

In the last five decades, and in particular after 1970, the Austrian income tax system underwent several significant structural changes. The most important structural reforms and developments pertain to the increasing differentiation between different types of income and to the tax unit. Before turning to the analysis of variations in the functional form of the tax tariff, we briefly sketch the most incisive reforms of the Austrian income tax.

2.1 Increasing differentiation between different types of income

Irrespective of our (yet-to-be-justified) interpretation of 1989 as the watershed year for the Austrian income tax tariff, a most significant structural reform within the Austrian income tax system occurred in 1993: the move towards a dual income tax (Lehner et al. 1993; Genser 1996). Since 1993/1994 interest income from bank deposits as well as dividend income paid to individuals and non-incorporated businesses are taxed at a proportional final withholding tax (“Kapitalertragsteuer I” for distributed dividends, “Kapitalertragsteuer II” for interest income), which was initially fixed at 22% and raised to 25% in 1997. A remarkable feature of the final withholding tax (which is even laid down in the Austrian Constitution) is that its level is coupled with the top income tax rate: it may not exceed half the prevailing top income tax rate (and must not fall below 20%). The 1993 tax reform was the last one in a series of several steps to tackle the massive evasion of taxation on interest income, made possible by the strict and constitutionally granted banking secrecy laws in Austria (Mooslechner 1994). Up to 1993, interest income had to be declared “voluntarily” within the assessed personal income tax and thus was taxed progressively under the general income tax scale; due to tax evasion, however, interest income practically remained untaxed. In 1984, an interest tax (“Zinsertragsteuer”) at a rate of 7.5% was implemented, which was not credited against the personal income tax liability (interest income was still liable for income taxation), but could be deducted as expenses from the taxable gross interest income (Mooslechner 1984). The interest tax, levied as a source tax, was cut to 5% in 1985 and abolished in 1987 following a decision of the Austrian Constitutional Court (Genser 1996). In 1989 a source tax on interest income of 10% was adopted, which was creditable against the assessed income tax liability. Along with a tax amnesty, this tax was finally replaced by the current system of a final withholding tax in 1993. Another noteworthy feature of the Austrian “Kapitalertragsteuern” is that they cover the inheritance tax for a broad range of equities, i.e., the final taxation of interest income and in many cases of dividend income also pertains to the inheritance tax (which was abolished in the middle of 2008).

With the aim of mitigating double taxation at the corporate and the shareholder level, the taxation of distributed dividends was changed several times since the end of the 1960s (Genser 1996). From 1987 on, distributed dividends were taxed at half the regular income tax rate. In 1994 the final withholding tax was extended to distributed profits from equity shares of domestic companies; this replaced the personal income tax liability. Since the reduction of the corporate tax rate from 34 to 25% in 2005, the combined effective tax rate on distributed dividends amounts to about 44%.

At this place, the comparison with Germany is interesting. After Austria’s union with the German Reich in 1938 the German tax code was adopted in Austria. It was basically left unchanged after World War II, so that the two countries started out with an identical income tax code 60 years ago. In contrast to the Austrian (to a certain extent) “dual” income tax, the German one by and large still can be characterized as a global income tax system.Footnote 3 Austria taxes interest income at a considerably lower rate compared to income earned through self-employment, dependent employment or pensions (Table 1). Dividend incomes are taxed at a combined rate of 43.75%. In addition, private capital gains are tax-exempt after a holding period of one year for equities in Austria (as in Germany). In an international perspective, the increasing digression from a comprehensive income tax in Austria is no exception. Most other EU member states, for example, have taken steps to exclude capital incomes from progressive taxation and to tax them at a proportional rate instead (Schratzenstaller 2004).

Another noteworthy long-term trend within the Austrian income tax is the increasing divergence between the taxation of incomes from dependent employment and from self-employment (Lehner 1973, 1974, 1981). Notably, this divergence has been caused by the holiday and Christmas bonuses (i.e., 13th and 14th monthly salaries in dependent employment), which are taxed only at symbolic rates, but also by tax reliefs for specific types of labor income (tax-free supplements for dirty, hard, dangerous, night, weekend and holiday work and overtime) and for employees (e.g., the employee’s tax credit or the traffic tax credit).

In Austria, social security pensions are also subject to wage income taxation (while pension contributions are tax deductible). In 2006, almost one-fourth (22.6%) of wage tax revenues came from the taxation of pensions (Statistik Austria 2007).

2.2 Tax unit and family status

In 1973, the Austrian income tax system was individualized by replacing the household as the tax unit by the individual taxpayer; this fundamental change was completed with the 1975 tax reform (Lehner 1973, 1974, 1981).Footnote 4 Before, three separate tax schedules existed for unmarried taxpayers, for married taxpayers, and for taxpayers with children. They had been introduced in 1946 and were replaced by two separate tax schedules for unmarried taxpayers and for all remaining taxpayers in 1967 (Neill 1985).

This reform was not only motivated by general socio-political considerations, but also by the scarcity of labor in the beginning of the 1970s: the replacement of joint income taxation of spouses by individual taxation aimed at eliminating negative work incentives for the second earner, whose income regularly was taxed at high marginal tax rates. With this move to individual income taxation Austria joined the majority of western industrialized countries taxing spouses individually. The only income tax relief taking into account taxpayers’ individual familial situation is the sole earner’s tax creditFootnote 5 (since 1973); in subsequent years supplements for children were introduced and increased repeatedly.

The system of tax reliefs for children was also changed several times (Lehner 1981, 1998; Lehner et al. 1993; Neill 1985): whereas until 1967 married couples with children benefited from lower marginal tax rates in the lower tax brackets, tax allowances for children were introduced in 1967, which were substituted by tax credits in 1973. In 1978 tax reliefs for children were abolished and replaced by direct transfer payments. In 1993 child tax credits were made payable (non-wastable) and have been raised several times since then. The sole earner’s tax credit, which originally had been granted to married employees only, was complemented by a sole parent’s tax credit in 1982.

Also in 1973 a number of personal tax allowances (e.g., for sole earners or for children) were replaced by personal tax credits for equity reasons by the then social-democrat government (Lehner 1973; Genser 1996). The aim was to avoid the degressive effects that tax allowances display within a progressive income tax schedule. Until today the absolute volume of tax relief caused by personal tax credits markedly exceeds that of personal tax allowances. Some of the personal tax credits (the employee’s tax credit introduced in 1973, the sole earner’s and the sole parent’s tax credit) were complemented by a negative income tax element in 1994, i.e., they are paid out in case of zero or low tax liabilities.

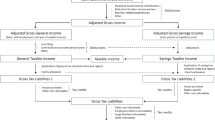

3 Statutory tax rates

In Austria, the income tax liability of an individual taxpayer in a given year is a function of his/her nominal taxable income in that year. The functional form of the income tax is specified in the income tax law (“Einkommensteuergesetz”, EStG). Austria applies—as many other countries do—a graduated tax schedule which in its current form (§ 33 (1) EStG, in the version of the Steuerreformgesetz 2005) comprises four income brackets and marginal tax rates of 0% (which applies to taxable incomes up to € 10,000), 38 1/3% (taxable incomes between € 10,001 and 25,000), 43.6% (taxable incomes between € 25,001 and 51,000), and 50%; the top bracket sets in at a taxable income of € 51,000. Within each bracket, the marginal tax rate remains constant, while the average tax rate increases with income. Notwithstanding all changes in the Austrian income tax system and in the tax tariff in particular, a stepped functional form has been in place since 1955.

To facilitate the description, we introduce a number of symbols. We denote the gross income by y and the income tax function as a function of gross income by T(y). It should be noted that the income tax function T need not coincide with the tax schedule as it appears or appeared in the law (which has taxable income as its independent variable). Rather, we take into account the detailed provisions of the EStG for calculating taxable income from gross income. Since the implementation of the second phase of the 2004/2005 tax reform (effective since 2005) marginal income tax rates as they are formally stipulated by the income tax law conform to the effective marginal tax rates and increase systematically with taxable income, as they by and large did before 1997. In the years between, effective tax rates differed from formal ones in a number of income brackets and displayed rather erratic fluctuations across incomes due to the calculation rules for the general tax credit, which was granted to every taxpayer (Breuss et al. 2004).Footnote 6

With income tax function T(y), we denote by T′(y) the marginal tax rate at gross income y, and by t(y): = T(y)/y the average tax rate.

3.1 Marginal tax rates

Figure 1 portrays the evolution of the marginal tax rate since 1955 for five levels of taxable income. Income levels are defined as proportions of per-capita gross wages of the various years (taken from National Accounts) net of social security contributions (which are fully tax deductible in Austria) as well as the standard (lump-sum) deductions to take into account work-related expenses (“Werbungskosten”) and special expenses (“Sonderausgaben”). The tax rates depicted in Fig. 1 (as well as all other tax rates and the measures and indicators used to characterize the long-term development of Austrian income taxation) pertain to incomes from dependent employment only. Our calculations account for the general tax credit and, thus, the effective marginal tax rates (after the tax credit) reported may deviate from the formal tax rates as set by the income tax tariff, as already mentioned. Apart from the general tax credit, neither further specific tax credits granted solely to employees (employee’s tax credit, traffic tax credit) nor family allowances nor the preferential proportional tax rate of 6% for holiday and Christmas bonuses (the so-called 13th and 14th salaries) are included in our calculations. In that sense, we report “inflated” marginal and average tax rates and also tend to overestimate the progressivity of the wage tax.Footnote 7

Figure 1 considers five comparable income levels: per-capita wages themselves, net of the deductions specified above (denoted by y, representing the “middle class”), half their level (y/2, the “relatively poor”), and twice (2y), five times (5y) and fifty times (50y) their level (“upper middle class”, “the upper class”, and the “rich”, respectively). This grouping follows Corneo (2005).

According to the latest wage tax statistics, the average yearly gross income of employees was € 25,797, the average yearly taxable income was € 17,651 in 2006 (Statistik Austria 2007). In comparison, yearly per-capita gross wages taken from National Accounts amounted to € 25,379 in 2006, per-capita wages net of the various deductions to € 20,619. Thus, for Austria per-capita wages are a better proxy for taxable incomes than is per-capita GDP (which Corneo uses in his analysis for Germany), the latter reaching € 31,140 in 2006. In 2006, 29% of the dependently employed had a gross income of up to half the per-capita gross wages (“relatively poor”), 27% were between € 12,000 and 25,000. At the upper end, yearly gross incomes exceeded € 100,000 for about 1.1% of all employees (the “upper class” and the “rich”; whereby only 0.1% of all dependently employed had a yearly gross income of above € 200,000; see Statistik Austria 2007).

As shown by Fig. 1, there has been remarkable intertemporal variation in the marginal tax rates since 1955. It is due to changes in the tax schedule and in the level of nominal incomes (and sometimes, both of them at once). Including the 1955 tax reform, the Austrian tax formula has been altered 13 times during the last five decades,Footnote 8 while GDP at current prices and the nominal wage incomes of the various classes with it have increased virtually each year.Footnote 9 Under a progressive tax schedule that is fixed in nominal terms, real income growth and inflation give rise to “bracket creeping”: taxpayers are pushed into higher tax rate brackets, so that effective income tax rates increase. As a tendency, the number of tax brackets in the Austrian income tax tariff has decreased over time, rendering bracket creeping a less important—although still non-negligible (see Section 6)—issue.

In summary, the development of marginal tax rates for all five income classes considered reveals a similar long-term trend. Departing from different levels, marginal tax rates are characterized by a rising trend until the end of the 1980s for all our income classes. This trend is most pronounced for the upper middle class: in contrast to the rich, the upper class, and the middle class, the upper middle class did not enjoy a period of relative tax stability between the end of the 1960s and the late 1980s. All income groups benefited from a rather sharp cut in the marginal tax rate in 1989. In contrast to the relatively poor and the middle class, the three upper income classes have experienced rather stable marginal tax rates afterwards.

On the whole, a pattern of converging marginal tax rates has been emerging over the last fifty years. Here, the closing gap between marginal tax rates for the rich and the poor after 1969 (the year in which this gap reached its maximum) is particularly striking: It went down from 51.1% points in 1969 to a historically low level of less than 7% points in 2000. While the latest income tax reform temporarily widened the spread between the rich and poor marginal tax rate in 2004 and even more so in 2005, it is reduced to less than 12% points from 2006 on. This effect is driven by the growth of nominal wages which makes the taxable income of the relatively poor exceed the tax-free income threshold of € 10,000.Footnote 10 Overall, the tax reform 2005 led to a further (and unprecedented) convergence of the marginal tax rates for all income groups, by and large as a corollary of changing to a tax formula with only three positive marginal tax rates lying within a quite narrow band (between 38 1/3 and 50%).

Thus, the long-term trend of converging marginal tax rates for different income groups is also the result of the continuing reduction of the number of tax brackets (which were broadened consequently) and therefore of marginal tax rates. The 1957 income tax tariff consisted of 19 tax brackets, which were reduced to 15 with the 1971 tax reform and to 12 with the 1973 tax reform (Lehner 1981). The most drastic reduction was effected by the 1988 tax reform, which halved the number of tax brackets from ten to five. The spread between the lowest and the highest marginal income tax rate as fixed in the income tax tariff (i.e., the formal tax rates), which reached its maximum at about 48% points in the 1971 income tax tariff, remained roughly constant at about 40% points between 1973 and 1989; afterwards it was depressed to 29% points (tax reform 2000) and to the already mentioned historically low level of about 12% with the 2004/2005 tax reform.

The incomes of the rich have been taxed at the top marginal tax rate according to the income tax tariff only from 1966 on, when their taxable income started to exceed the top income threshold, which was then fixed at two million Austrian Schilling (about € 145,000).Footnote 11 As shown by Fig. 1, the top marginal tax rate, T′(50y), for the rich today is roughly the same it was in 1955 (50% relative to 49.6%). In the meantime, however, there was a stable period with a tax rate of 53.1% (1957 till 1965), a subsequent steady increase (1966–1972) to almost 63%, another rather long period of stable high rates (62% from 1973 till 1988), and a drastic cut in 1989 to the current level of 50%.Footnote 12

The marginal tax rate for the upper class, T′(5y), was significantly below the top marginal rate in 1955 (about 39%). This discrepancy even increased with the decrease of the marginal tax rate for the upper class in 1958/1959 before it then narrowed due to a strong increase in the upper class’ marginal tax rate until the late 1980s. Since 1989, the upper class has, as the rich, been taxed at the top marginal tax rate. This reflects the fact that the top income threshold, above which the top marginal rate applies, has practically remained constant since 1989 at a level of about € 50,000. An increasing fraction of taxpayers has thus faced the top marginal rate during the last decades. Whereas in 1955 you had to earn about 159 times the average taxable income (according to our definition) to face the top marginal rate, nowadays even taxpayers earning about 2.5 times the average taxable income are taxed at the top marginal tax rate.

For taxpayers in the middle classes, with income between average per-capita wages and twice that level, marginal tax rates tended to increase from 1955 until the late 1980s, peaking at 55% for the upper middle class. In 1989 they fell markedly to 42%, a level at which they have more or less rested till today. Virtually the same pattern holds for average income earners, however at tax rates that were 10–20% points lower. A remarkable phenomenon is the rather high discrepancy between T′(y) and T′(2y) of about 22% points between 1984 and 1987. The 1988 tax reform significantly reduced the marginal tax rates of the middle classes. Since then, marginal tax rates have remained rather stable for the upper middle class, but have increased by over 6% points for the middle class, so that the gap to the upper middle class has become rather small.

The relatively poor (y/2), who started at a zero marginal tax rate in 1955 overall experienced steadily increasing marginal tax rates between 1965 and 1988 (with a maximum of 28% in 1980 and 1981). After the 1988 tax reform marginal tax rates dropped to 22%, to increase again to rather hefty levels of over 43% (2000–2003). The latest tax reform reduced the relatively poor’s marginal tax rate to zero in 2005; it has, however, almost returned to its historical high level of the beginning of this decade in 2006. The drop of the marginal tax rate to zero in 2005 (see Fig. 1) was caused by the increase of the tax-free taxable income from € 8,800 to 10,000; the following sharp increase to 38 1/3% in 2006 is due to the fact that the taxable income of the relatively poor exceeded this tax-free income in 2006. Remarkably, thus, the relatively poor have experienced the most drastic increase of marginal tax rates during the past half century.

3.2 Average tax rates

Figure 2 displays the intertemporal pattern followed by average tax rates. Overall, the picture is one of increasing curves that, except for the rich (whose average tax burden remained roughly constant between the beginning of the 1970s and the end of the 1980s), moved almost parallel until 1989 when all income classes experienced a significant drop in their average tax rates. With the exception of the poor’s tax rate, which was halved in 2000 and has decreased to almost zero in 2006, and the constant average tax rate of the rich, average tax rates have been slightly increasing since 1989.

As shown by Fig. 2, all groups carry a higher tax burden at the end than at the beginning of the period. The increase is quite similar (16–19% points) for the three income groups in the middle (the middle class, the upper middle class, and the upper class), whereas the rich experienced a moderate increase by four percentage points only. The increase of the tax burden during the 1960s and the 1970s was especially dramatic for the middle to the upper class. The poor’s average tax burden, which was at zero until the middle of the 1960s, increased significantly in the subsequent years to reach a peak of about 16% in 1986 before it then steadily went down back to almost zero until 2006.

Economic reasoning suggests that the income tax (at least its wage tax component) significantly impacts on incentives to work through substitution and income effects. Changes in marginal tax rates (at constant average tax burdens) make work less rewarding, relative to other activities, inducing individuals to substitute away from labor. Changes in average tax rates (at constant marginal tax rates) cause income reductions that would induce individuals to work more to maintain consumption levels. With a grain of salt, Figs. 1 and 2 indicate co-movements of the marginal and the average tax rates for each income group over time. This leaves it unclear whether substitution or income effects dominate, rendering definitive conclusions about how work incentives were affected by changes in Austrian income taxation impossible (at least from the rather crude prima-facie evidence we are considering here).Footnote 13

The 1988 tax reform entailed a significant decrease of marginal and average tax rates for all income classes. The largest cuts were experienced by the three income classes: the upper middle class (decrease of the marginal tax rate by 14% points and of the average tax rate by almost 10% points), the upper class (decrease of the marginal tax rate by 8% points and of the average tax rate by about 11% points) and the rich (decrease of the marginal and of the average tax rate by 12% points). In this case, work incentives were strengthened by the reform for all income groups; particularly, however, for the three upper income classes. The reforms of 2000 and 2004/2005 work in the opposite direction for the poor: they decrease work incentives by raising the marginal tax rate from 22% in 1999 to 43.3% in 2000 and—after a temporary drop in 2004/2005—to 38 1/3% in 2006. Also for the middle and the upper middle class marginal as well as average tax rates increased slightly from 2005 on. At the same time, the average tax burdens for these income groups fell only slightly.

4 Progressivity measures

To analyse the redistributive effects produced by the Austrian income tax schedule, we look at two measures of tax progressivity: the coefficient of residual progression and the net income ratio.

4.1 Coefficient of residual progression

The coefficient of residual progression ρ(y) is a local measure of tax progressivity; it is defined as the elasticity of net income with respect to taxable income. Tax progressivity exists at a given income level y whenever ρ(y) < 1. The smaller the coefficient of residual progression, the higher is the degree of local progressivity. Figure 3 depicts the somewhat erratic pattern of the coefficient of residual progression for our five income classes. As expected, most coefficients are smaller than one. Exceptions of ρ(y) = 1 apply to the poor until 1964 and again in 2005, but this is an irrelevant artifact as their average and marginal tax rates were zero then.

A few observations are worth commenting. First, the rich are the only income group for which local tax progressivity has been steadily falling since the beginning of the 1970s, after short intervals of increasing progressivity in the end of the 1950s and the mid-1960s. Since the early 1970s, the rich are the income group with the lowest degree of local progressivity. Second, the upper class and the upper middle class have been hit by the highest degrees of local progressivity.Footnote 14 In particular, the coefficient of residual progression was at or below the very low level of 0.7 in the mid-1980s for the upper middle class. Third, local progressivity for the relatively poor remained in the range between 0.85 and 0.9 for most of the time period analysed, with the exceptions of the early 1970s and 2000s. Fourth, the 1988 tax reform caused a steady decrease and convergence of local tax progressivity for the three middle groups (the middle class, the upper middle class, and the upper class). Fifth, compared with corresponding figures for Germany in Corneo (2005), the Austrian scheme exhibits a wider range for the coefficient of residual progression and, on average, lower values (i.e., higher degrees of progressivity).

4.2 Net income ratios

Net income ratios provide further information on the redistributive effect of the income tax. For any two levels of income y and y’, we define the net income ratio asFootnote 15 \( r(y,y') = \frac{1 - t(y)}{1 - t(y')}. \)

In an interval (y′, y), there is incremental progressivity at the income range if r(y, y′) < 1. In this case, the relative gap between after-tax incomes, [y−T(y)]/[y′−T(y′)], is smaller than the relative gap between pre-tax incomes, y/y′. Conversely, r(y, y′) > 1 for y > y′ implies incremental regressivity. The smaller the net income ratio at a given income range, the stronger is the degree of incremental progressivity. Figure 4 shows how net income ratios evolved for various income ranges defined by an intertemporally constant gross income ratio y/y′.

According to Fig. 4, r(y, y′) has always been smaller than unity for all income ranges; this implies incremental progressivity. However, as before two sub-periods can be clearly distinguished: From 1955 to 1989, incremental progressivity increased moderately by and large across all income ranges (except for the rich with respect to the upper class). The 1988 tax reform enacted a strong reduction in tax progressivity across all income ranges; since then incremental progressivity has been more or less stable. Noteworthy, the position of the rich improved, relative to the starting point in 1955—although that improvement was not a steady one and gained momentum only after the 1973 tax reform.

As an overall trend, the bandwidth of the net income ratios for the income ranges has been narrowing over the past five decades. Looking, e.g., at the developments of r(2y,y), r(5y,y), and r(50y,y), and observing the relative constancy of r(2y,y), the narrower range indicates that the Austrian income tax code has, from the viewpoint of an average income earner, become less progressive over time.

5 Distributive effects of the latest income tax reform 2004/2005

Against the backdrop of a “secular” tendency towards reduced progressivity in the Austrian income tax, a closer look at the distributive effects of the most recent income tax reform, enacted in two phases in 2004 and 2005, might be of some interest. As evidenced by our previous figures, the distributional impact of that reform, which involved a reduction in the number of tax brackets and also adjustments of the marginal tax rates in each bracket, is not a priori clear: movements of average and marginal tax rates as well as progressivity indexes show a mixed picture.

The subsequent analysis changes the focus from relative positions in the income distribution to absolute levels of incomes. As a benchmark for our comparison we choose the year 2000, when the previous tax reform had been enacted. Let t 2000(y) denote the average tax rate for taxable income y in 2000, such that x 2000(y) = [1−t 2000(y)] y is the net income in that year. Similarly, net income after the implementation of the second phase of the 2004/2005 tax reform is denoted as x 2005(y) = [1 − t 2005(y)] y. The 2004/2005 tax reform induces a tax reduction which causes the rate of growth of net income, given a certain taxable income y, to be equal to

Generally, distributional neutrality of a tax reform (in the sense that relative income rankings remain untouched) requires the rate of growth of net incomes to be identical for all income levels. A tax reform is “progressive” [“regressive”] (in the sense of Lorenz-dominance) if the growth rates of net income are smaller [larger] for high taxable incomes than for low ones (i.e., if Δ n (y) is decreasing [increasing] in y).

A first look at the growth rates of net income Δ n (y) across income levels in Table 2 clearly indicates that the recent Austrian tax reform was progressive: it raises after-tax incomes of the lower incomes at higher rates than after-tax incomes of the middle and higher incomes. While at a taxable income of € 10,000 the growth rate of net income reaches 9%, it rapidly decreases to slightly more than 1% at taxable incomes of € 40,000. Taxpayers with incomes of € 50,000 and more experience almost no increase of their net incomes.

The last column of Table 2 contains the rates of growth of real net incomes, defined by

where \( \tilde{y} = y/\left( { 1 + \Uppi } \right) \) with (1 + Π) as a deflator equals the level of nominal income in 2000 that is equivalent in purchasing power to nominal income y in 2005. By Π we denote the aggregate rise in the price level between 2000 and 2005; its value has been fixed at 8%. Although the growth rate of real income falls behind that of nominal income, the progressive character of the tax reform shows up again. As incomes in the middle and upper range only experienced a small tax relief, the growth rates of real net incomes for these groups even became slightly negative.Footnote 16

Thus, measuring the effects of the 2004/2005 tax reform by referring to absolute income levels (possibly deflated), we conclude that it almost exclusively favored low-income earners, whereas higher income levels hardly benefited. Nevertheless, as the analysis in the previous sections indicated, from the perspective of relative income inequality, the distributional effects of the most recent Austrian tax reform are (still) unclear.

6 The evolution of income tax revenue and its composition

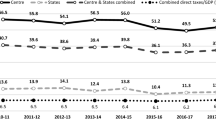

Figure 5 depicts the evolution of the revenue of the Austrian income tax as a fraction of GDP since 1959, also (for sake of reference and comparison) including revenues from the corporate tax and the tax on industry and trade (“Gewerbesteuer”), which was abolished in 1994. Revenues from the personal income tax include revenues from the wage tax (levied on income from dependent employment and on pensions), from the assessed income tax (largely consisting of taxes on the income of the self-employed), and revenues from the taxation of dividend income (final withholding tax on dividends; “Kapitalertragsteuer I”) and interest income (final withholding tax on interest; “Kapitalertragsteuer II”).

Departing from similar shares in GDP in the end of the 1950s (around 2%), the revenues from the wage tax and the assessed income tax, the two most important components of the personal income tax, display quite different long-term trends. Wage tax revenues have increased steadily in the time period considered, from less than 2% of GDP in 1959 to almost 7% in 2006. After reaching a peak of almost 3% of GDP in the middle of the 1960s and the 1970s, respectively, revenues from assessed income tax declined continuously afterwards to about 1% of GDP in 2006.

The revenues from the taxation of interest income via a separate interest tax, which was introduced in 1984, increased markedly afterwards as a consequence of the diverse reforms enacted after 1989. They reached a high of almost 1% of GDP in the middle of the 1990s to decline slightly afterwards to a more or less stable level of about 0.5% of GDP in the last few years.

The share of corporate taxes in GDP fluctuated around 1% of GDP between the middle of the 1960s and the beginning of the 1980s and remained more or less stable somewhat below this level until the mid-1990s. In the subsequent years the shares almost doubled due to several tax reforms (increase of the corporate tax rate in 1994 and diverse measures to broaden the tax baseFootnote 17), but have been stagnating during the last years.Footnote 18

Total revenues from the income tax steadily increased over time—with a temporary drop in 1989 as a consequence of the 1988 tax reform—and reached a peak of about 10% of GDP in 2001 (see also footnote 20).

Combining the observations on tax revenues and tax rates nicely illustrates the effect of “cold progression” for the period since 1989: average tax rates have remained more or less constant for given positions in the income distribution while average tax payments (as proxied by the ratio between tax revenues and incomes) have been increasing. There are several potential explanations for this, such as less tax evasion, fewer tax expenditures, rising revenues from the taxation of pensions, or an increase of the labor income share in GDP. We could not find any evidence for any of these causes to prevail. Rather, what seems at work here is the bracket creeping effect of stepped tax tariffs, together with its corollary, namely increasing average tax rates within brackets. More Austrians moved into the higher tax brackets (an effect potentially advanced by inflation),Footnote 19 thereby delivering higher shares of their income to the government.Footnote 20 Cold progression typically is seen to have an inequality-reducing effect; in Austria this might have worked against the tendency of the tax system to become less progressive over time.

Figure 6 tracks the composition of total income tax revenues, i.e., the shares of wage tax, assessed income tax, and income taxes on interest and dividends in total income tax revenue, over time. Assessed income tax, with a share of 55% in total income tax revenues the largest sub-tax within Austrian income tax in the end of the 1950s, has continuously lost in importance since. Its share went down to about one-fourth in the end of the 1970s and to about one-fifth in the mid-1980s. Since the beginning of the 1990s assessed income tax revenues as a fraction of total income tax revenues have steadily declined and reached a historical low of 11% in 2006. This development dates back to institutional changes (tax refunds from annual wage tax adjustments, which were subtracted from wage tax revenues before 1994, are subtracted from assessed income tax revenues since then), but also to the introduction of tax reliefs effecting a certain “erosion” of the income tax: most recently, the introduction of tax breaks for R&D and training measures or the preferential tax treatment of retained profits of sole-proprietorships and partnerships.Footnote 21 Not least, the increasing spread of tax rates for incorporated firms on the one hand and non-incorporated ones on the other hand might have induced the latter ones to change their legal form and thus might have depressed assessed income tax revenues.

Wage tax, on the other hand, has gained by far the largest weight in Austrian income tax during the past 50 years. Starting at a share of 44% in total income tax revenues in 1959, it climbed to a share of about three-fourth until the end of the 1970s, which went down slightly to about 70% after the 1988 tax reform. In the subsequent years its share remained rather constant at somewhat more than 70% to increase again since the end of the 1990s. In 2006 wage tax accounted for almost 80% of total income tax yields.

Whereas revenues from dividend taxation have been slightly increasing, but altogether more or less negligible throughout the whole period under consideration, the reforms of interest taxation after 1989 brought about an increasing contribution of the taxes on interest income to overall income tax revenues. Revenues from the interest tax as a fraction of total income tax revenues peaked at 10% in the mid-1990s and have been slightly decreasing afterwards; to reach a share of 6% in 2006.

The changing structure of total income tax revenues dates back to several factors: a structural change of the labor force (i.e., a decreasing share of self-employed in the long run), a growing volume of taxable pensions, an increase in tax expenditures for the income tax, and the introduction of the withholding tax on interest incomes.

7 Interpreting the evidence

Interpreting the evolution of the Austrian income tax, as it is reflected in the evidence presented above, leads to a multi-faceted picture. As in most other policy areas, the development of the income tax is driven by interwoven considerations of political feasibility, economic and fiscal viability, and distributional concerns. It is difficult to identify a clear line in the past 50 years of Austrian income tax history; several interpretations are conceivable. By way of an example, one might view the overall reduction in tax rates and the moderation of tax progressivity since 1989 as evidencing the “neoliberal” tendency to cut back overall government influence, to sharpen economic incentives, and to erode concerns for equality and social justice. However, whether the 1988 tax reform has really increased the incentives to work (recall that average tax rates have fallen, too) or tamed the government (revenues as a share of GDP have not fallen) seems debatable.

In spite of this ambiguity, the general trends of Austrian income taxation can perhaps be summarized as follows:

In terms of its fiscal significance, the income tax gained in stature over the past 50 years. Revenues out of the income tax as a percentage of GDP have—apart from some dips—risen steadily. In that respect, the Austrian trend differs markedly from the German one, where Corneo (2005) sees the income tax to be in decline. The “Queen of Taxes” is still in good shape in Austria, at least in its capacity to fill governmental coffers.

In its capacity as a policy instrument, the income tax (at least its tariff structure) seems to have lost popularity among politicians. Changes in the formal tax tariff have become significantly less frequent recently. Parts of the legislators’ activities may have shifted away from manipulating the tariff to less visible tinkering with the tax base and its definition. Income tax reforms are always controversial, and the tax tariff is the most prominent and (allegedly) easiest-to-understand component of the income tax law. Politicians might have simply become too anxious to touch it after 1989. It appears, however, that the alternative to changes in the tax rate—changes in the tax base, which are less transparent for taxpayers and voters—was not pursued in a consistent manner: whereas the 1988 tax reform, for example, considerably broadened the income tax base, subsequent years brought about several reforms in both directions.

In terms of income types, the once comprehensive Austrian income tax has evolved towards a wage (and pension) tax. Capital incomes have been “outsourced” from the progressive income tax scale, and incomes other than those from employed labor have lost much of their earlier significance as tax items.

In terms of its incentive aspects on labor supply, the Austrian income tax system shows no clear tendency. Within income groups, average and marginal tax rates typically move in the same direction, generating substitution and income effects that tend to offset each other.

In terms of its distributional impact among taxpayers, the Austrian income tax has, in a sense, become “more proportional” and “less egalitarian” since 1989. The 1988 income tax reform, which explicitly aimed at cutting the formerly high marginal tax rates while broadening the tax base by reducing or abolishing tax reliefs (Lehner 1988), marks the turning point. At least for the above-average income groups, the differences between marginal and average tax rates have been narrowing, and several measures signal a reduction in progressivity. This might, in parts, have been compensated by the cold progression effect that growth and inflation transported more Austrians from the middle classes into higher tax brackets, as the coincidence of increasing tax revenues and constant average tax rates indicates. Generally, the redistributive effectiveness of the Austrian income tax (proxied by its progressivity) seems to have faded significantly since the 1990s.

Notes

The next income tax reform is envisaged for 2010.

The divergence in the factual evolution of the German and the Austrian income tax is remarkable also against the backdrop that the tax systems in both countries have a common origin (dating from 1938) and, despite some more recent deviations especially in the area of personal income taxation, continue to be quite similar (Doralt and Ruppe 2007, pp. 15ff).

Also in the German income tax, there are several digressions from a comprehensive system: the taxation of only half the dividend income and of capital gains within the progressive tax tariff as well as the exemption of capital gains from income taxation after a holding period on one year. From 2009 on, a final withholding tax of 25% will be levied on all kinds of capital income (dividend income, interest income, and capital gains).

By contrast, Germany—as one of meanwhile very few western countries—since 1958 applies a system of marriage subsidization in its income tax code by allowing full income splitting for spouses.

The sole earner's tax credit replaced the sole earner's tax allowance, which had been introduced in 1967.

The general tax credit was abolished with the latest income tax reform and integrated into the income tax tariff.

The implication of the preferential taxation of holiday and Christmas bonuses is substantial: it brings the effective top income tax rate for employees down from 50% to about 43%. The total tax relief produced by this provision amounted to € 5.3 billion in 2006, compared to total wage tax revenues (including payments by pensioners) of about € 18.1 billion.

Reforms were effective as of 1955, 1958, 1962, 1967, 1969, 1971, 1973, 1975, 1979, 1983, 1989, 2000, and 2005; changes that do not affect the tax schedule (as variations of tax allowances, for example, or the introduction of the final withholding tax for interest and dividend incomes) are not considered.

The average growth of GDP amounted to 7% per year between 1955 and 2006; nominal wages per employee increased by 6.1% per year.

The tax-free income threshold (basic allowance) was increased in 2005 from € 8,800 to 10,000.

The top marginal tax rate according to the 1955 income tax tariff was 63.72% for single taxpayers (between 2 and 5.139 million Austrian Schilling) and 61.36% (for taxable incomes above 5.139 million Austrian Schilling), respectively. It was reduced to 55.46% in 1957 and reached its maximum at 62.88% in 1971. The 1973 tax reform decreased the top income tax rate to 62%, its current level of 50% was introduced with the 1988 tax reform.

In the 1970s, considerably higher marginal tax rates were discussed in Austria. E.g., Genser and Holzmann (1979) analyze a then popular proposal by trade unions to tax top income earners at marginal rates of 80%. However, they find that this proposal (which was never implemented) would have remained without any significant distributional impact.

To the authors' knowledge, no empirical studies exist that disentangle the income and substitution effects of (income) tax reforms on labor supply in Austria. While estimates of wage rate elasticities of labor supply for Austria are available, approximating the effects of income tax changes through such wage elasticities would, however, be misleading in the presence of a progressive income tax tariff.

This phenomenon is sometimes ridiculed as “Mittelstandsbauch” (middle class belly) in the German literature.

This definition differs from the formula used in Corneo (2005). He defines tax progressivity by R(y, y′) < y/y′, where R(y, y′) = r(y, y′) y/y′. This progressivity assessment is equivalent to ours, but using r(y, y′) facilitates comparisons for different income pairs (since, e.g., proportionality is given when r = 1, independently of the levels of y or y′).

Above the top income threshold of € 51,000 the tax reduction in absolute terms amounts to € 165 per year in 2005 against 2003.

This includes the introduction of a minimum corporate tax for companies without taxable profits. In addition, the Austrian National Bank is liable for corporate income taxation since 1994, which also increased corporate income tax revenues.

The peak in 2001 can be explained by a special effect due to the introduction of interest charges on tax arrears, which influenced the temporal distribution of corporate tax revenues (the same effect can be observed for the assessed income tax). In 2005 the corporate tax rate was cut from 34 to 25%, accompanied by a very moderate broadening of the tax base and the introduction of a group taxation, which will curb revenues also in the following years.

This happened although the number of tax brackets has been reduced over time (see Section 3.1), which generally eases the problem of bracket creeping. However, as the marginal tax rate in the lowest tax bracket is rather high and the income threshold above which the top tax rate is applied has not been increased since 1989, cold progression still has considerable effects.

Before 1989 such an effect is not so obviously detectable from the graphs as during this period the increase in tax revenues went parallel to an increase in marginal and average tax rates.

These permanent tax reliefs were complemented by several temporary measures, e.g., tax reliefs for incremental investment.

References

Auer R (n.y.) Steuerrechtliche Tabellensammlung (loose leaf; current issue: July 2008). LexisNexis ARD ORAC, Vienna

Breuss F, Kaniovski S, Schratzenstaller M (2004) The tax reform 2004/05—measures and macroeconomic effects. Austrian Econ Q 9:127–142

Bundesministerium der Finanzen (2008) Die wichtigsten Steuern im internationalen Vergleich (2007 edition). Bundesministerium der Finanzen, Berlin

Corneo G (2005) The rise and likely fall of the German income tax, 1958–2005. CESifo Econ Stud 51:160–186

Doralt W, Ruppe H-G (2007) Grundriss des österreichischen Steuerrechts, vol I, 9th edn. Manz, Vienna

Genser B (1986) Steuerprogression: Konzepte und empirischer Befund für Österreich. Forschungsbericht 8602, Ludwig Boltzmann Institut für Analysen wirtschaftspolitischer Aktivitäten, Vienna

Genser B (1996) Austria’s steps towards a dual income tax. In: Muten L, Sorensen PB, Hagen KP (eds) Towards a dual income tax?. Kluwer, London, pp 69–89

Genser B, Holzmann R (1979) Einkommensteuerreform. Eine quantitative Analyse. Reihe Volkswirtschaft Nr. 21, Institut für Wirtschaftswissenschaften, University of Vienna

Lehner G (1973) Zur Reform der Einkommensteuer. WIFO Monatsberichte 46:49–58

Lehner G (1974) Zur Lohn- und Einkommensteuersenkung 1975. WIFO Monatsberichte 47:360–366

Lehner G (1975) Zur Lohn-und Einkommensteuersenkung 1975. WIFO Monatsberichte 48:360–366

Lehner G (1981) Analyse der Einkommensteuertarife 1957 bis 1983. WIFO Monatsberichte 54:561–578

Lehner G (1988) Die Steuerreform 1988. WIFO Monatsberichte 61:610–622

Lehner G (1998) Familienförderung neu geregelt. WIFO Monatsberichte 71:865–871

Lehner G, Breuss F, Mooslechner P, Puwein W, Schebeck F, Wüger M (1993) Die zweite Etappe der Steuerreform. Austrian Institute of Economic Research, Vienna

Mooslechner P (1984) Die Einführung einer Zinsertragsteuer (ZESt) in Österreich. WSI-Mitteilungen 37:719–725

Mooslechner P (1994) Steuerreform und Finanzmärkte: Kapitalertragsbesteuerung und Kreditsteuer. WIFO Monatsberichte 67:42–49

Neill JD (1985) Die Lohnsteuer und ihre Aushöhlung. Eine Analyse über Zusammensetzung, Ausmaß und Kosten der Erosion des österreichischen Lohnsteuertarifes zwischen 1964 und 1985. Dissertation, Vienna

OECD (2008) Taxing wages 2006–2007. OECD, Paris

Schratzenstaller M (2004) Towards dual income taxes—a country-comparative perspective. CESifo DICE Report 2(3):23–30

Schratzenstaller M (2007) Unternehmensbesteuerung in der Europäischen Union—aktuelle Entwicklungen und Implikationen für die deutsche Steuerpolitik. DIW Vierteljahrshefte zur Wirtschaftsforschung 76(2):21–38

Statistik Austria (2007) Statistik der Lohnsteuer 2006. Statistik Austria, Vienna

Acknowledgments

We thank Dietmar Klose for valuable research assistance and Otto Farny, Hans Pitlik, Anton Rainer, Peter Rosner, and an anonymous referee for helpful suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schratzenstaller, M., Wagener, A. The Austrian income tax tariff, 1955–2006. Empirica 36, 309–330 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-008-9087-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-008-9087-y