Abstract

Purpose

Urban soils’ variability in the vertical direction presumably affects hydrological parameters at the timescale. Moreover, horizontal soil alterations at small spatial scales are common in urban areas. This spatio-temporal variability and heterogeneity of soil moisture and the possible influencing factors were to be described and quantified, using data of a soil monitoring network in the city of Hamburg, Germany.

Materials and methods

Soil moisture data from ten observation sites within the project HUSCO was evaluated for two different years. The sites were located within districts with different mean groundwater table depths and characteristic urban soil properties. Soil hydrological simulations with SWAP were calculated for a selected site.

Results and discussion

The temporal evolution of soil water content and tension for the sites was very distinct, related to soil substrate, organic matter content, and groundwater table depth. Impacts of different vegetation rooting depths, the soil substrates’ type, and to some extent the degree of disturbance on soil water dynamics could be identified. An impact of groundwater table depth on the water content of the topsoil during low-precipitation periods could be assumed. The comparison of the results of soil hydrological simulations with empirical data indicated an overestimation of infiltration and percolation for the given soil substrates.

Conclusions

While soil properties are mainly determinant for the long-term progression of soil hydrology, local site factors affect the short-term regime. A shallow groundwater table contributes to more constant water dynamics while the relative decrease of water during a dry phase is diminished.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Although urban areas constitute only a small percentage of the total used land, they are a contemporary research topic as their properties influence the daily lives of more than half of the world’s population (54 %) living in cities (United Nations 2014). By building both the basis for and the source of numerous processes and characteristics, urban soils are a main component within the urban ecosystem (Blume 1998). They are known to be archives of cultural history, as historic as well as recent impacts of human activity can be back traced in urban soils, resulting from different anthropogenic influences on soil genesis and transformations (Burghardt 1994). The extent of these soil modifications in urban areas varies broadly with regard to types of urban land use and impact intensity (Pickett and Cadenasso 2009). Analyzing more than one hundred soil profiles within one city, Greinert (2015) found extremely different soil properties within a distance of several dozen meters; however, not all properties of urban soils in his studies were strongly varied when areas with similar use and construction are regarded. Nevertheless, urban soils can be highly variable within small spatial scales and feature typical characteristics, e.g., different bulk densities due to soil compaction, varying contents of organic matter, or patchy distribution of coarse natural or man-made materials such as large gravel or construction waste (Lehmann and Stahr 2007). In combination with groundwater and surface water managing and the local percentage of soil sealing, these features are important determinants for soil water dynamics and urban hydrology. Recent studies focus on sealed soils in urban areas (a detailed review can be found in Scalenghe and Marsan 2009), infiltration processes, and the urban water management system (e.g., Mohrlok et al. 2008; Barron et al. 2013), or report on urban soil’s physical, chemical, and biological properties (Scharenbroch et al. 2005). Besides urban pedosphere, also its adjacent spheres like atmosphere and biosphere have special urban anthropogenic properties (Endlicher 2011), contributing to the multifactorial and diverse impacts on urban soils as well (e.g., shown for flora in Bechtel and Schmidt 2011). Yet, specific studies on urban soil water dynamics are sparse. Here, the role of the specific properties of urban soils as well as the functions of groundwater-level management and its relation to capillary rise on soil water dynamics are of interest; however, they have not been the focus of research for urban areas until now.

Apart from that, in non-urban environments, groundwater capillary rise and evapotranspiration from the soil surface have been investigated in fieldwork at a local and regional scale (Nachabe et al. 2005; Logsdon et al. 2009; Yeh and Famiglietti 2009) and in models (Maxwell and Kollet 2008). It was shown that groundwater acts as a soil water source when the water depth lies within a critical zone (Soylu et al. 2011) and therefore subsequently delivers water for surface water flux and evaporation (Chen and Hu 2004). As soils are an exchange medium for water and energy, and thereby are able to influence the local climate, research on soils within the urban environment furthermore needs more consideration to improve the predictability of future urban climate in the context of climate change and urbanization (Umweltbundesamt 2008) and to contribute to adaptation strategies for town planning.

Linking to this, a deeper understanding of the relevance of soils, their usage, and their functions for the local urban climate system is the overarching objective of the project “Hamburg Urban Soil Climate Observatory,” HUSCO (Wiesner et al. 2014). By running a measurement network of meteorological and pedological sensors within the city of Hamburg, data on water and energy budgets of diverse urban soils under different urban land use and with contrasting groundwater levels is provided. The present study aims to quantify the temporal heterogeneity of urban soil water dynamics. The range of their hydrological characteristics as a function of soil properties, groundwater table depth, and urban land use is to be analyzed. Key objectives of this study are to improve insights (1) by quantifying the temporal variability of soil moisture contents and water potentials for two different vegetation periods for ten different suburban sites, (2) by identifying the role of urban soil properties and site-specific impacts in controlling trends of soil water dynamics, and (3) by analyzing the effects of a dry phase on the topsoil moisture contents. Additionally, (4) model simulations of soil water contents and fluxes at a selected site are compared with observations in order to identify the specific advantages of modelling approaches for studying urban soil water dynamics and their controls.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Site description

The data evaluated in this study was collected from ten monitoring sites from the research project HUSCO within the city of Hamburg, Germany. It is located in northern Germany (53° 33′ N, 10° 0′ E), situated on the river Elbe 110 km southeast of the North Sea coast, and it covers an area of 755 km2. The climate is predominantly marine, characterized by a moderate air temperature amplitude, mild winters, moderately warm summers, and high wind speeds (von Storch and Claussen 2010).

Measurement sites were selected out of two urban districts with similar size and land use structure, but which differ in mean groundwater level (Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg 2010). One district features a shallow mean groundwater table (<2.5 m below surface on average), the other a deep one (>5 m below surface on average). The deep groundwater district is also located closer to the city core, but with comparable distance to rural surroundings. However, local differences of the groundwater depth occur within the districts, due to groundwater management measures.

Furthermore, within each district, the measurement sites were located in two urban land use types, namely urban green space, i.e., a pasture area, and single housing development, i.e., detached houses with extensive backyards. These urban land use types represent 7.8 % (green space) and 21.5 % (residential buildings) of the total area of the city of Hamburg (Statistisches Amt für Hamburg und Schleswig-Holstein 2014). Categorizing them into the scheme of local climate zones (LCZ) by Stewart and Oke (2012), compared with results from Bechtel and Daneke (2012), they match the LCZ field/low plants with 0 to 5 % surface sealing ratio, and regular housing/open low rise with about 50 % surface sealing ratio, respectively. The sites are named according to the district with “S” (shallow groundwater table district) and “D” (deep groundwater table district) and by reflecting land use with the suffix “_G” (green space) and “_H” (housing areas).

2.2 Monitoring sites, instrumentation, and data handling

Details on the sites including soil type, vegetation, and soil texture are listed in Table 1. To allow for urban soil characteristics, anthropogenic impacts are listed as well. Some of the soil profiles contain construction waste in the substrate of horizons below the humic topsoil. Others showed perturbed horizons or deposited allochthonous material. The studied sites were classified according to Lehmann and Stahr (2007), with regard to their degree of disturbance (DoD): Two sites are man-influenced soils (category 1), containing little or no artifacts (≤1 %) that have often experienced mixing of soil horizons, and six sites are man-changed soils (category 2), with significant contents of coarse fragments and organic matter, layering and/or residues from past or modern settlements. Two sites were assigned to the category of natural urban soils (category 0).

All study sites were instrumented with devices for soil water and temperature monitoring (for the locations, see Fig. 1). Soil moisture monitoring was done with tensiometer probes for monitoring soil water tension (SWT) for all stations and either with separate probes measuring volumetric water content (VWC) and soil temperature, or a combined probe for both values. A list of sensor types installed at the profiles is provided in Table 2. Additionally, the site D_G1 provided local precipitation data from a meteorological measurement station installed there.

The sensors were installed in the undisturbed soil profile at 5, 10, 40, 80, and 160 cm depths below the surface, unless limited by the shallow groundwater table or administrative restriction. Data were collected automatically with a temporal resolution of 30 min (Table 2); data analysis was performed with this entire data set unless stated otherwise. The observation periods of this study include data of VWC and SWT from 01 April to 31 October for the years 2011 and 2013. All station setups included a pedological description considering the official German pedological mapping guidelines (Ad-hoc-Arbeitsgruppe Boden 2005). The sampling of disturbed (one collection) and undisturbed soil samples (five parallels) according to standard procedures considered measurement depths and horizontal distinction. Subsequent laboratory analysis was carried out as given in Table 3. The soil organic matter (SOM) content was estimated by measuring the total organic carbon (TOC) content (Waksman and Stevens 1930); root density was assessed using the estimation described in Ad-hoc-Arbeitsgruppe Boden (2005). The local groundwater depth (Table 1) was ascertained during fieldwork in early winter 2010 and assumed to be the maximum water table depth.

VWC readings with CS616 sensors were temperature-corrected according to the producer’s manual (Campbell Scientific Inc. 2006). To improve the comparability between both VWC sensors, the Decagon 5TM readings needed to be corrected to fit the results of the CS616 sensors. The correction is based on a linear regression of the data of a parallel instrumented soil profile, providing the correction function

with y = VWC Decagon 5TM corrected and x = VWC Decagon 5TM reading.

The applied tensiometers provide a measuring range of +1000 hPa (pressure) to −850 hPa (tension) which resulted in missing values in phases of higher soil water tension. Thus, in graphics depicting SWT, values higher than pF2.9 (i.e., 850 hPa) are referred to as >pF3.

To make the soil hydrological data of the different profiles easier to compare, the measured VWC was normalized using the soil-specific residual VWC (the permanent wilting point as determined in the laboratory) and the saturated water content (porosity). The resulting parameter, namely the relative volumetric water content Θ, therefore is calculated as

with θ = measured VWC, θ r = residual VWC, and θ s = VWC at saturation. Further information on the measurements at the HUSCO stations, the measurement techniques, and data handling and evaluation can be found in Wiesner (2013).

An estimation of the available water content (AWC) within a soil column down to 40 cm depth (topsoil) was calculated to assess the plant available water within the densely rooted soil layer. A third-degree polynomial fit matching the values derived from laboratory analyses of undisturbed samples provided an approximation for the water that is potentially available within the soil. The integrated water content is calculated as the integral of this polynomial function from 0 to 40 cm. With this method, the water within the soil column at a certain date was estimated, e.g., before and at the end of a defined time period for the calculation of water loss during a phase without rain.

2.3 Meteorological data

In Table 4, selected meteorological data for 2011, 2013, and a 30-year mean in Hamburg are given, as recorded at the station Hamburg-Fuhlsbüttel (data: Deutscher Wetterdienst). The two years primarily differ regarding their distribution of rainfall, whereas the precipitation sum is of a comparable amount. While in 2011, spring (March, April, May) with only 54 mm of rain was unusually dry compared to the 30-year mean value, in 2013, the precipitation for the same season summed up to almost four times that quantity. In contrast, in summer 2013, less than half of the rain (133 mm) of the summer 2011’s precipitation was recorded. Fall 2011 again was drier with only about 40 % of the 30-year mean rain sum.

In terms of air temperature averages and solar radiation, spring 2011 was a mild and very sunny season, while in 2013 it was 3.4 K cooler during this season. On the other hand, with an air temperature of 0.3 K above average, during the dry and warm summer of 2013, 1.4 times as much sunshine hours (733 h) were noted compared to the rainy summer of 2011, being 0.2 K cooler than the long-term mean.

2.4 SWAP hydrological simulations

To calculate soil moisture distribution and fluxes, the open-source model SWAP, version 3.2, as distributed by Alterra (Kroes 2008) was applied. This quasi 2D model describes transport processes of water, nutrients, and thermal energy in the vertical direction. In addition, lateral water movement in terms of drainage and runoff, runon respectively, can be observed. Soil water flow is calculated with Richards’ equation solving it numerically with an implicit, backward, finite difference scheme. The model’s scopes of application are mainly agriculturally used soils and wood.

The specification and input parameters that were used for the simulation run of the site D_G1 are given in Table 5. The results were compared with the observations of Θ and SWT to investigate the applicability of a modelling approach with SWAP for studying urban soil water dynamics.

3 Results

3.1 Dynamics of soil water content and matrix potential

3.1.1 General temporal dynamics

Characteristic soil hydrological features for vegetation periods in temperate latitudes are a high initial soil water content in spring due to residual water from winter precipitation (snow and ice melt), a comparably dry summer season, and a rewetting of soil in fall (Illston et al. 2004). This shape of a typical course of water content in soil will be referred to as the “sinusoidal annual cycle.” It is mainly caused by meteorological characteristics in mid-latitude areas and modified by soil physical properties and vegetation.

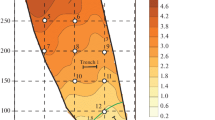

The soil profiles studied within HUSCO differ noticeably from each other in substrate, soil physical properties, and organic matter content (see Table 1 for details). The time-depth evolution of the relative water content Θ and SWT within the 2011 vegetation period are given in Figs. 2 and 3; the data of 2013 are shown in Figs. 4 and 5, respectively. These graphics are a result of linear interpolation between the data of five measurement depths. For rainfall, the daily data of the measurements at Hamburg-Fuhlsbüttel (data: Deutscher Wetterdienst) are shown as reference.

First of all, the impact of the precipitation’s distribution and amount within the vegetation period on the soil moisture dynamics is noticeable. Starting at April 1st with low SWT for all sites (Figs. 3 and 5), further evolution is generally driven by phases with stronger rainfall, e.g., in July 2011 and mid May 2013. Here, all sites depict a reduction of SWT at least in the upper layers. In general, 2011 was an untypical year in terms of the temporal distribution of precipitation. Thus, the expected sinusoidal annual cycle of Θ and SWT could not be identified clearly (Fig. 2) and, instead, a forward shift of maximum drying towards the early summer months (May/June) was evident, caused by a dry spring period with a sequence of three weeks without precipitation followed by single days with intensive rainfall of up to 10 mm per day. Additionally, a rather abrupt end of summer’s low Θ could be identified at many stations, due to intensive and long-lasting rain in August. The following fall with poorer precipitation again caused some drying in the upper layers.

During the vegetation period of 2013, on the other hand, a rainy spring delayed the drying of soil until early summer (Fig. 4). With only very little precipitation in July and August (as described in Section 2.4 and Table 4), the decreased Θ in greater depths resumed until late fall as October’s precipitation did not sufficiently restock below the topsoil. This was even more obvious in SWT measurement data (Fig. 5).

3.1.2 Impact of groundwater table depth

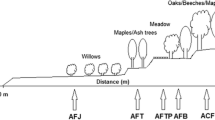

To detect differences in soil hydrology with regard to groundwater levels, the measurements at two green spaces that are used as pasture areas were evaluated, as similar land, analogous vegetation types, and no local groundwater control measures ensure better comparability (for more details, see Table 1).

A long-lasting period of little precipitation, as observed in spring 2011 and summer 2013, led to a topsoil drying at all green space stations, caused a loss of relative volumetric water content Θ respectively (Figs. 2 and 4). Yet, the time during which this drying was evident as well as the depth to which it persisted varied. Two prominent relevant factors could be identified from local site properties: (a) groundwater level and (b) rooting depth of vegetation.

For sites with a shallow groundwater table of approximately 40 cm below the surface (S_G1 and S_G2), the water tension SWT remained constantly low at pF2.0 and less throughout both years while Θ showed some signs of drying close to the surface. Depending on the depth of the rooting zone and the root density (higher at S_G2 due to trees), the relative water content decreased down to 0.2 in 10-cm-depth measurements for short time periods in summer 2011 and fall 2013 following the weeks with little rain. At the pasture grass site S_G1, Θ reached values of 0.4 in topsoil in 2011 and 0.25 in 2013. For the grass-covered profile S_G3 with a lower groundwater table in this district of about 1.2 m below the surface, nearly constant water content was observed below 40 cm depth. Slightly more intensive variations in the topsoil could be made out, compared to S_G1. At this measurement station, also SWT (Figs. 3 and 5) revealed signs of dryness in all depths, yet most prominently down to 10 cm, reaching values of about pF2.7.

On the contrary, sites D_G1, D_G2, and D_G4, at which the groundwater table depth is located deeper than the measurement depth (below 1.6 m), showed a pronounced reduction of Θ in topsoil as well as deeper soil layers, reaching almost residual water content values (Θ nearly 0) in both vegetation periods (Figs. 2 and 4). Most striking is the intensive loss of water content in the areas of the rooting depth, as it is located in 50 cm at D_G1 and D_G4, and in 110 cm at D_G2. Data on SWT (Figs. 3 and 5) confirmed this notice as water tension temporarily rose up to pF2.9 or higher (beyond measuring range) in these depths for prolonged time.

3.1.3 Differentiation by soil substrate

The substrates at the observed soil profiles vary from sand (D_G4) to loamy sand and from loamy horizons (e.g., D_H2) to high SOM/peat (S_G1). Apart from general particle size distribution differences, various soil horizon properties could be made out, resulting from soil genesis as well as anthropogenic impacts like compaction or the incorporation of construction waste or allochthonous material (DoD 1 or 2, Table 1). For the differentiation of soil water dynamics by urban soil substrate, a focus lay on the effect of single horizons with nontypical properties. Within the housing areas, the substrates at two sites featured coarse to medium sand particle sizes (D_H1 and S_H1) which are associated with high hydraulic conductivities. Thus, Θ was lower in general and less variable throughout the observation periods 2011 (Fig. 2) and 2013 (Fig. 4). Percolation appeared to take place more rapidly and with only short-time effect on water content at deeper horizons. Yet, short-time decreases in SWT after heavy precipitation within the topsoil (D_H1) and even down to depths below 80 cm (S_H1) became apparent.

On the contrary, soil profiles nearby with a stagnic horizon, i.e., the slowly permeable loamy material in 50 cm depth at D_H2 or the high soil bulk density layer in 110 cm depth at S_H2, revealed areas with enduring high Θ. The soil water accumulates in the dense atop horizon in late summer 2011 and spring 2013, coupled with intensive precipitation refilling through the overlying sandy horizons during these seasons, as also apparent in SWT data (Figs. 3 and 5). Moreover, the dense horizons prevent a replenishment of underlying horizons after long drought, which became visible in late 2013 after little precipitation in summer: Starting in August, Θ remained at values of 0.3 or lower (Fig. 2 and 4) and precipitation events were hardly able to restock water contents in depth, creating a rather sharp line between the stagnic horizons and the soil below with nearly unaffected Θ and SWT (Figs. 5 and 6)

A further extreme in soil substrate that was observed by the measurements was a high SOM. At sites S_G1 and S_G2, peaty topsoil horizons were present. The water content at these site was controlled by the near-surface groundwater level (Section 3.1.1) as well as by the high SOM (Table 1), which determined a high pore volume (>65 %) and very low bulk density (0.7 g cm−3, data not shown). No intensive drying in scales comparable to other sites could be observed here, best visible in SWT data (Figs. 3 and 5). Values above pF1.5 are rare at these two soil profiles, independent from periods with little precipitation. Rainfall or its absence had a rather slow impact on Θ of the topsoil here (Figs. 2 and 4) as water content changes only slightly after precipitation and remains at reduced values for longer times. Single heavy rains are not apparent in topsoil Θ but more prominent in SWT, probably due to the logarithmic scale of pF values (Figs. 3 and 5).

Another main common characteristic of urban soils is the existence of coarse material such as large gravel or construction waste (DoD 2). At the observed study sites, it most notably occurred at green space site D_G2 with about 25 % of construction waste in the upper 100 cm. At the housing areas soil profiles, a content of 5 to 10 % of it was found at S_H1 down to 50 cm, and at D_H2 in the upper 60 cm (Table 1). Nevertheless, water dynamics within the vegetation periods of 2011 and 2013 (Figs. 2 to 5) do not show identifiable schemes or characteristics that could be attributed to this anthropogenic coarse material itself, yet differences are visible. The dynamics of water content Θ as well as the progression of SWT throughout the years and after special occasions like drought or heavy rain do not allow conclusion on the impact of the allochthonous soil skeleton here. Instead, Θ and SWT progress very distinctly, ranging from lasting stagnant water to rapid drainage within the concerned horizons at the three sites.

3.2 Case study: three weeks of dryness

Data of a period with no precipitation was evaluated to trace differences in topsoil drying and their possible dependence on urban soil characteristics and site properties. From 12 April to 03 May 2011, three weeks without rain in the entire observation area led to a shortfall in the rewetting of upper soil horizons. The consequence was a loss of water within the topsoil at all sites, owing to evapotranspiration from the surface and percolation to the subsoil. This decrease of water (loss in mm), calculated as the difference between the measured water contents at the beginning and the end of the dry phase, was set into relation to the soil’s capacity to store water within the regarded layers (surface down to 40 cm depth), i.e., the AWC (Fig. 6).

Apparently, there was a clustering of soils within each of the two districts. The loss of stored water at the sites of deep groundwater district D tended to be higher in absolute values, ranging from 29 mm at D_G2 up to 62 mm at D_G1. At the shallow groundwater district, the decrease of soil water content spanned from 14 mm at S_H1 and S_G3 to 21 mm at S_H2. Given that the AWC of the upper 40 cm within the soil profiles at district D is lower in general compared to that of district S, the percentage loss of water on the total AWC is even considerably higher: At district D, the decrease during the dry phase came to 39 to 66 % of the topsoil’s AWC, while at district S, the soil water reduction added up to only 11 to 26 %.

Considering the soils’ performance with regard to their urban DoD, there was no obvious impact. In district S, the lowest loss in relative values was observed at sites without anthropogenic impacts, i.e., natural urban soils S_G1 and S_G2. Yet these soils feature high SOM as well, involving a high water-holding capacity and AWC respectively. The second lowest decrease was at S_H1, a man-changed soil with substantial alterations in substrate and soil layering. It is noteworthy that this site’s groundwater table was, unlike what was expected in this district, below measurement depth during the installation of the measurement site (Table 1).

Striking is the fact that at all sites of shallow groundwater district S, even without a local groundwater level near the surface and featuring a sandy substrate and a high degree of disturbance (DoD 2, site S_H1), a lesser loss of water in absolute as well as relative values occurred, compared to deep groundwater district D.

3.3 SWAP simulations

The model simulations of vertical soil water fluxes were carried out at site D_G1. This soil was addressed as a Stagni-Gleyic Cambisol, characterized by a substrate of mainly sandy loam, with a topsoil SOM of 12 % and the occurrence of construction waste within the upper 30 cm of about 8 % (Table 1). As the soil material of the upper layers was anthropogenically transferred in the course of surface modelling, this profile was assigned to DoD category 2, man-changed soils. Selected input parameters that were used for this model simulation are listed in Table 5.

For the years 2011 to 2013, the observations at the instrumented site (Fig. 7) roughly showed the sinusoidal annual cycle of water content Θ, with varying intensity. Resulting from spring 2011 and summer 2013 dryness, the soil dried notably in the following months, reaching values of Θ = 0.4 or less down to 80 cm. By contrast, in 2012, no extended period without precipitation occurred. Therefore, an intensive and deep drying of soil did not happen as rainfall events frequently interrupted the loss of water in the upper layers. Throughout the entire observation period, the precipitation of rainfall events or short phases with a larger amount of rain recognizably percolated down to about 80 cm, visible in Θ reaching values of 0.8 or higher, as well as in low SWT (pF1.0 or less) for several days.

Comparing the results of the model simulation (Fig. 8), the progression of soil water dynamics was obviously distinct from reality. First of all, there appeared to be no major difference between the three years. From early spring to early winter, topsoil was severely dry down to 40 cm (Θ of 0.2 or less) and drought remained constant even in deeper areas (in 80 cm depth still Θ of 0.35). Meanwhile, SWT was correspondingly high. Furthermore, precipitation events did not have a clearly identifiable impact apart from very transient slight increases in water content down to 40 cm depth (Θ up to 0.3 and SWT down to about 2.5, i.e., barely within field capacity). No prominent fluctuations due to infiltration from water or phases of intensive evapotranspiration are detectable in the simulated data. Only during winter time, when air temperature and thus potential evaporation was low, a rewetting of the topsoil occurred, depending on the intensity of winter precipitation. Additionally, very implausible was the sharply zoned progression of the water dynamics, visible in Θ as well as in SWT.

Precipitation at reference station (top) and SWAP simulation of the 2D time-depth evolution of relative volumetric water content Θ (center) and soil water tension SWT [pF] (bottom) at soil profile D_G1 for the years 2011, 2012, and 2013 (linear interpolation between modelled values at the measurement depths)

An additional output of SWAP simulations, apart from soil profile data on instantaneous fluxes of drainage, root extraction, water and solute, is a detailed overview of water balance components for each simulated year (Table 6). For 2011, a slight positive storage change of 0.76 cm was calculated, while the other two years resulted in a net loss of soil water (−2.97 and −3.75 cm). Transpiration values exceeded soil evaporation, amounting to about 1.5 times the evaporation value. No interception, runon, or seepage was calculated.

4 Discussion

4.1 Impacting factors

A number of apparent factors that had an influence on the spatial and temporal variability of urban soil water dynamics could be identified with the evaluated data.

The proximity of groundwater to the soil surface influenced the urban soil hydrology at the observed sites: Very shallow groundwater led to constant high Θ and low SWT, most likely induced by capillary rise. As the soil profile depth was only about 40 cm, this water rise involved all soil horizons until near-surface. Thus, only slight signs of topsoil drying were visible. By contrast, soils with a deep groundwater table depth showed a more distinct variation of soil hydrological parameters and very intensive loss of water contents in the course of the observed years. Especially the lower soil areas experienced severe drying as a rewetting from rainfalls could not be sufficient.

Apart from this immediate availability of water, the vegetation’s consumption of storage water played an important role during the vegetation periods. In particular, the rooting depth of deciduous trees could be clearly identified as the lower boundary of decrease in water content. The uptake of water through tree roots led to larger deficits in Θ below 10 cm depth in both observed years, compared to grass vegetation. This difference in the source area of water for different plant species was studied for rural areas in numerous studies, e.g., mature trees (saplings, mature trees) used water from deeper soil layers than grasses in a temperate savanna (Weltzin and McPherson 1997). Holmes and Colville (1970) noted that both short-term and seasonal fluctuations in deep soil water can indicate root activity for forest as well as grassland, while evapotranspiration from forest during winter and spring was up to 2.2 times that from grassland. However, in the study of James et al. (2003), soils were driest under grasses at 10 and 30 cm depth at the end of the growing season, compared to shrubland and trees. In the present study, only a line of trees and a sparse forest, respectively, were observed instead of a dense forest, which is a possible explanation for this difference in the results. Yet, the short-time variability under grass was higher compared to that under tree vegetation, this observation being consistent with other studies focusing on non-urban areas. For example, McLaren et al. (2004) found temporal heterogeneity over the growing season in depths down to 30 cm to be significantly greater under grasses than under woody plants.

Presumably also a loss of rainfall reaching the soil and infiltrating as a result of interception might contribute to this more intense drying at sites vegetated by trees compared to nearby sites with grass (D_G2 and S_G2 versus D_G1 and S_G1). Studies on interception loss observed a loss of 29.3 % of gross rainfall for leafed canopy, e.g., deciduous trees in summer (Herbst et al. 2008), or season-long loss of 18.8 % with single events ranging 9.4 to 89.0 % (Price and Carlyle-Moses 2003).

The urban specific anthropogenic alterations in soil structure and the modifications of substrate appeared to be of high relevance for soil water dynamics, too. Expectedly, according to soil physical properties, mainly sandy substrates like S_H1 or D_G4 exhibited fast drainage and low water contents. Stagnic horizons (D_H2 and S_H2) induced all-year high water contents in overlying soil layers while obstructing seepage. Regarding the pedological urbanity, in terms of compacted layer or allochthonous substrate in general, a degree of disturbance (DoD 1 or 2) can be an impacting factor for soil water dynamics. Yet the presence of man-made material alone (as a contribution to DoD 2) is no sufficient evidence and did not show an unambiguous impact on hydrological parameters. Rather, the entire formed soil profile with aligning factors of substrate variation results in modified hydrological dynamics. Apart from that, urban natural soils (no degree of disturbance) revealed that high organic matter content is of certain relevance, mainly for soil physical parameters like available water capacity or saturated water contents, Θ respectively.

Distinguishing between land uses, the sites did not show different patterns (e.g., similar progression of D_G4 and D_H1). Apparently, urban use of soils alone had no impact on water dynamics. Still, it is closely related to technogenic disturbance of soils and thereby influences hydrology in an indirect manner. Furthermore, a surface sealing—which was not under investigation in this study—is very likely to locally influence infiltration and evapotranspiration, as studies on sealing ratio and soil hydrology showed (e.g., Wessolek and Facklam 1997).

It can be assumed that at the individual sites the performance of soil water is the result of a synergy between multiple impacting factors. At sites D_G1 and D_G2, the observed pronounced reduction of Θ in deeper soil layers was caused by a combination of intensive percolation due to high hydraulic conductivities of the inferior layers, by vegetation’s root water uptake, as well as by a missing refilling from percolating water from the upper layers. Likewise, at S_G1 and S_G2, high groundwater level and natural soil horizons with high SOM jointly contribute to the attenuated soil hydrological progression, like higher and more constant water contents and little variations in SWT. This impact of soil properties on temporal soil moisture variability and patterns is described in many studies for different scales (e.g., Robock and Vinnikov 2000; Western et al. 2002) and has been monitored for non-urban land use soils in case studies. For example, the surface soil moisture mapping project SGP97 and follow-ups (Famiglietti et al. 1999) found consistencies in differing mean moisture content and variations in soil type, vegetation cover, and rainfall gradient.

A distinct effect from low-precipitation periods, associated with a lack of water refill from the surface, could be made out at all sites. This effect appeared to be varying in its intensity according to the districts’ mean groundwater table depth. Concurrently, it was nearly independent from the urban land coverage. The observations made in the three-week-long dry phase in April 2011 showed that in soil with shallow groundwater within the topsoil, a mean decrease of only 15 % of AWC occurred. At the same time, an average of 50 % of AWC was lost in soils with a deep groundwater table. Apparently, the reason for differences in topsoil drying is multifactorial as well: One important contributor is the groundwater table depth, presumably leading to a refilling as far as the soil substrate promotes this process. This effect was shown for instance in models, simulating groundwater to act as a source for soil water near the surface when the water depth lies within a critical zone (Maxwell and Kollet 2008). However, another considerable factor observed is the dependence of AWC from soil substrate and structural properties. These are generally attributed to anthropogenic impacts, e.g., bulk density and pores. Therefore, the DoD also might play a rather prominent role in the causal chain, yet does not necessarily do so.

4.2 Quality of simulation results

The soil hydrology simulation of the selected site D_G1 describes roughly the course of soil water contents and tension for the three considered years. A sinusoidal annual cycle was visible, and short-time impacts of precipitation could be made out. However, there were obvious deficits in the current state of the soil model: Summer rainfall did not percolate into the soil deep enough. Thus, it could not contribute to a longer-lasting increase in Θ and a lowering of SWT. Concurrently, topsoil drying was too strong and distinct with implausibly sharp boundaries. This distinction appeared to be more like a stagnic horizon, which was not parameterized. Additionally, generally, the soil water tension’s simulation was predominantly inaccurate, overestimating drying depth and intensity. The results on water balance components appeared to be very rough and not detailed enough to be plausible.

The anthropogenic impact cannot be visible in this model result as the major deficits are not eliminated, yet. The parameterization appears to be very sensitive and needs to be carried out very carefully. As the urban and anthropogenic impact factors are part of soil horizon properties, they need to be implemented with awareness of the relevance of each parameter, e.g., substrate or rooting density. Therefore, the aim to identify specific advantages of modelling results for urban soils and their controls could not be achieved, yet. Deficiencies in the simulation of urban soils with little vegetation may originate from the diverging objective of SWAP, being an application for the simulation of agricultural and woodland soils.

5 Conclusions

Water dynamics of urban soils are the result of the synergy of multiple variables and show a distinctive spatial and temporal variability. A quantification of the temporal variability was achieved in the present study, allowing for several conclusions on the impacting factors. First and foremost, the soil substrate and pore size distribution determines the general progression of soil water movements over time. In natural urban soils, the soil functions remain unmodified, while in anthropogenic urban soils, the degree of disturbance can, but do not have to, be a relevant controlling factor. While alterations in bulk density and layering lead to a serious influencing of soil hydrological performance in the course of the year, the presence of construction waste and man-made material does not inevitably do so. Thus, it cannot be stated that an anthropogenic substrate is a sufficient criterion for an urban-influenced soil hydrology. Moreover, location factors like vegetation roots and groundwater table depth are highly relevant for the decrease of water content during dry phases and the rewetting coupled with precipitation events. In conclusion, while soil properties are mainly determinant for the long-term progression of soil hydrology, local factors like vegetation or heterogeneous precipitation affect the short-term regime.

From the results of this study, several projections can be deduced: Presumably, a shallow groundwater table contributes to higher and more constant relative water content in the soil column. The relative decrease of water during dry phases is diminished. Additionally, the organic matter content of the topsoil was recorded to increase the available water content. Thus, modifying or degrading soils and natural substrate could lead to alterations in water storage, as horizons high in SOM are often anthropogenically removed in cities, increasing the degree of disturbance. This possibly leads to a loss of key soil functions like high field capacity.

Regarding soil hydrology simulation attempts with SWAP, urban soils cannot be easily parameterized for hydrological simulations by using soil mapping information on horizons and substrate alone.

A concluding general finding of the HUSCO soil monitoring network concerns the spatial distribution of urban soils: They are often attributed in a locally very restricted manner. Thus, there can be a high small-scale variability within very short distances, appearing in soil properties and therefore in soil hydrology as well.

References

Ad-hoc-Arbeitsgruppe Boden (2005) Bodenkundliche Kartieranleitung. Schweizerbart’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Stuttgart

Barron OV, Barr AD, Donn MJ (2013) Effect of urbanisation on the water balance of a catchment with shallow groundwater. J Hydrol 485:162–176

Bechtel B, Daneke C (2012) Classification of local climate zones based on multiple earth observation data. IEEE J Sel Top Appl Earth Observ Remote Sens 5:1191–1202

Bechtel B, Schmidt KJ (2011) Floristic mapping data as a proxy for the mean urban heat island. Clim Res 49:45–58

Blume HP (1998) Böden. In: Sukopp H (ed) Stadtökologie - Ein Fachbuch für Studium und Praxis. Fischer, Stuttgart

Burghardt W (1994) Soils in urban and industrial environments. Z Pflanzenernähr Bodenkd 157:205–214

Campbell Scientific Inc (2006) CS616 and CS625 water content reflectometers instruction manual. Campbell Scientific, Inc, Logan, Revision 8/06

Campbell Scientific Inc (2010) Model 107 temperature probe instruction manual. Campbell Scientific, Inc, Logan, Revision 6/10

Chen X, Hu Q (2004) Groundwater influences on soil moisture and surface evaporation. J Hydrol 297:285–300

Decagon Devices Inc (2010) 5TM water content and temperature sensors: operator’s manual. Decagon Devices, Inc, Pullman, Version 0

DIN-ISO10694 (1996) Bodenbeschaffenheit - Bestimmung von organischem Kohlenstoff und Gesamtkohlenstoff nach trockener Verbrennung (Elementaranalyse)

DIN-ISO11277 (2002) Bestimmung der Partikelgrößenverteilung in Mineralböden – Verfahren mittels Siebung und Sedimentation

Endlicher W (2011) Introduction: from urban nature studies to ecosystem services. In: Endlicher W et al (eds) Perspectives in urban ecology. Springer-Verlag, Berlin

Famiglietti JS, Devereaux JA, Laymon CA, Tsegaye T, Houser PR, Jackson TJ, Graham ST, Rodell M, van Oevelen PJ (1999) Ground-based investigation of soil moisture variability within remote sensing footprints during the Southern Great Plains 1997 (SGP97) Hydrology Experiment. Water Resour Res 35:1839–1851

Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg (2010) Daten des höchsten/niedrigsten Grundwasserflurabstands für Hydrojahre 1995/1996. Behörde für Stadtentwicklung und Umwelt - Amt für Gewässerschutz (U1), Hamburg

Greinert A (2015) The heterogeneity of urban soils in the light of their properties. J Soils Sediments 15:1725–1737

Hartge KH, Horn R (2009) Die physikalische Untersuchung von Böden. E. Schweizerbart’sche Vertragsbuchhandlung, Stuttgart

Herbst M, Rosier PTW, McNeil DD, Harding RJ, Gowing DJ (2008) Seasonal variability of interception evaporation from the canopy of a mixed deciduous forest. Agric For Meteorol 148:1655–1667

Holmes JW, Colville JS (1970) Forest hydrology in a karstic region of southern Australia. J Hydrol 10:59–74

Illston BG, Basara JB, Crawford KC (2004) Seasonal to interannual variations of soil moisture measured in Oklahoma. Int J Climatol 24:1883–1896

IUSS Working Group WRB (2015) World reference base for soil resources 2014, update 2015: international soil classification system for naming soils and creating legends for soil maps. World Soil Resources Reports No. 106. FAO, Rome

James SE, Partel M, Wilson SD, Peltzer DA (2003) Temporal heterogeneity of soil moisture in grassland and forest. J Ecol 91:234–239

Klute A, Dirksen C (1986) Hydraulic conductivity and diffusivity. Laboratory methods. In: Klute A (ed) Methods of soil analysis—part 1, vol No 5, Physical and mineralogical methods: Soil Science Society of America Book Series. Soil Science Society of America, Madison, pp 687–734

Kroes J (2008) SWAP Version 3.2—theory description and user manual. Alterra, Wageningen

Lehmann A, Stahr K (2007) Nature and significance of anthropogenic urban soils. J Soils Sediments 7:247–260

Logsdon SD, Hernandez-Ramirez G, Hatfield JL, Sauer TJ, Prueger JH, Schilling KE (2009) Soil water and shallow groundwater relations in an agricultural hillslope. Soil Sci Soc Am J 73:1461–1468

Maxwell RM, Kollet SJ (2008) Interdependence of groundwater dynamics and land-energy feedbacks under climate change. Nat Geosci 1:665–669

McLaren JR, Wilson SD, Peltzer DA (2004) Plant feedbacks increase the temporal heterogeneity of soil moisture. Oikos 107:199–205

Mohrlok U, Wolf L, Klinger J (2008) Quantification of infiltration processes in urban areas by accounting for spatial parameter variability. J Soils Sediments 8:34–42

Nachabe M, Shah N, Ross M, Vomacka J (2005) Evapotranspiration of two vegetation covers in a shallow water table environment. Soil Sci Soc Am J 69:492–499

Pickett STA, Cadenasso ML (2009) Altered resources, disturbance, and heterogeneity: a framework for comparing urban and non-urban soils. Urban Ecosystem 12:23–44

Price AG, Carlyle-Moses DE (2003) Measurement and modelling of growing-season canopy water fluxes in a mature mixed deciduous forest stand, southern Ontario, Canada. Agric For Meteorol 119:69–85

Richards LA (1948) Porous plate apparatus for measuring moisture retention and transmission by soil. Soil Sci 66:105–110

Robock A, Vinnikov KY (2000) The global soil moisture data bank. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 81:1281

Scalenghe R, Marsan FA (2009) The anthropogenic sealing of soils in urban areas. Landsc Urban Plan 90:1–10

Scharenbroch BC, Lloyd JE, Johnson-Maynard JL (2005) Distinguishing urban soils with physical, chemical, and biological properties. Pedobiologia 49:283–296

Statistisches Amt für Hamburg und Schleswig-Holstein (2014) Statistische Berichte - Bodenflächen in Hamburg am 31.12.2013 nach Art der tatsächlichen Nutzung, Hamburg

Soylu ME, Istanbulluoglu E, Lenters JD, Wang T (2011) Quantifying the impact of groundwater depth on evapotranspiration in a semi-arid grassland region. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci 15:787–806

Stewart ID, Oke TR (2012) Local climate zones for urban temperature studies. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 93:1879–1900

UMS GmbH (2009) User manual T4/T4e pressure transducer tensiometer. UMS GmbH, Munich, Version 06/2009

Umweltbundesamt (2008) Böden im Klimawandel- was tun?! In: Schönemann N (ed) UBA-Workshop, 22nd/23rd January 2008. Umweltbundesamt, Dessau

United Nations 2014: world urbanization prospects: the 2014 revision, highlights (ST/ESA/SER.A/352). UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs - Population Division

von Storch H, Claussen M (2010) Klimabericht für die Metropolregion Hamburg. Springer Berlin, Heidelberg

Waksman SA, Stevens KR (1930) A critical study of the methods for determining the nature and abundance of soil organic matter. Soil Sci 30:97–116

Weltzin JF, McPherson GR (1997) Spatial and temporal soil moisture resource partitioning by trees and grasses in a temperate savanna, Arizona, USA. Oecologia 112:156–164

Wessolek G, Facklam M (1997) Site characteristics and hydrology of sealed areas. Z Pflanzenernähr Bodenkd 160:41–46

Western AW, Grayson RB, Bloschl G (2002) Scaling of soil moisture: a hydrologic perspective. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci 30:149–180

Wiesner S (2013) Observing the impact of soils on local urban climate. Ph.D. Thesis Thesis, University of Hamburg, Hamburg

Wiesner S, Eschenbach A, Ament F (2014) Urban air temperature anomalies and their relation to soil moisture observed in the city of Hamburg. Meteoreol Z 23:143–157

Yeh PJF, Famiglietti JS (2009) Regional groundwater evapotranspiration in Illinois. J Hydrometeoreol 10:464–478

Acknowledgments

The data used in this study was collected within the project “Hamburg Urban Soil Climate Observatory” (HUSCO). The project is funded by DFG as part of the cluster of excellence “Integrated Climate System Analysis and Prediction (CliSAP)”, KlimaCampus, Hamburg. Furthermore, financial support was granted by the Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg, Leitstelle Klimaschutz. We also acknowledge the landowners, who allowed us to deploy and run our measurement stations on their ground: Tierpark Hagenbeck Gemeinnützige Gesellschaft mbH, Hamburg, Germany; ISUF e.V., Hamburg, Germany; the Thoms, Hansen, and Hurtig families; the Gymnasium Albrecht Thaer; and the city of Hamburg (Bezirksamt Eimsbüttel and Hamburg-Nord).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Paulo Pereira

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Wiesner, S., Gröngröft, A., Ament, F. et al. Spatial and temporal variability of urban soil water dynamics observed by a soil monitoring network. J Soils Sediments 16, 2523–2537 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-016-1385-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-016-1385-6