Abstract

Simultaneous extraction of the coal and gas is an effective method of eliminating coal mine gas disasters while safely exploiting the coal and achieving efficient gas drainage in China, which is widely accepted by the main coal-producing countries around the world. However, the concrete definition of simultaneous extraction is vague and there is little accurate theoretical support for the simultaneous extraction of coal and gas, which makes it difficult to determine an efficient gas drainage method appropriate to the features of coal seams. Based on theoretical analysis, laboratory tests and field observations, a specific definition of simultaneous extraction of coal and gas is proposed after analyzing the characteristics of coal seam occurrences in China, and we developed the mechanism of mining-enhanced permeability and established the corresponding theoretical model. This comprises a process of fracture network formation, in which the original fractures are opened and new fractures are produced by unloading damage. According to the theoretical model, the engineering approaches and their quantitative parameters of ‘unloading by borehole drilling’ for single coal seams and ‘unloading by protective seam mining’ for groups of coal seams are proposed, and the construction principles for coal exploitation and gas-drainage systems for different conditions are given. These methods were applied successfully in the Tunlan Coal Mine in Shanxi Province and the Panyi Coal Mine in Anhui Province and could assure safe and efficient simultaneous extraction of coal and gas in these outburst coal mines.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

China is the largest coal-producing country in the world, with an output of 3.68 billion tons in 2013 (National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China 2014). Coal mine gas, with main component of methane, also known as coal-bed methane (CBM), is associated with coal seams (Authorized Committee of Coal Science and Technology Term 1996; Cheng et al. 2010). As mining depth and intensity increase, mining geology and technical conditions are becoming increasingly complicated. Coal seam gas has become the key factor that constrains safe and efficient production of coal mines. In addition, coal and gas outbursts and gas explosion accidents are still the most serious hazards in coal mines (Cheng et al. 2010; Wang et al. 2012a). Coal seam gas is also a strong contributor to the greenhouse effect and is approximately 25 times more potent than CO2 (IPCC 2007; Wang and Cheng 2012; Wang et al. 2014). Because coal mine gas is also a clean and efficient energy resource (Flores 1998), direct emissions of this gas not only waste a valuable energy resource but also pollute the environment (Yuan and Naruse 1999; Xie et al. 2011a). In China, resources of CBM are very abundant: at 2000 m depth, its volume is 36.81 × 1012 m3, which is almost equivalent to the amount of conventional gas present (Yuan et al. 2012). Gas drainage during the exploitation of coal resources can promote safe coal production and achieve the goals of clean energy use and greenhouse gas reduction (Cheng et al. 2011; Wang et al. 2013). Finding an effective method of coal mine gas drainage and utilization and achieving safe and efficient simultaneous extraction of gas and coal have therefore become topics of significant research efforts in the field of safe coal mine production.

To safely and efficiently exploit coal resources, gas drainage should be firstly carried out, thereby transforming high gas content coal seams with outburst risks into low gas content coal seams (Noack 1998; Creedy and Tilley 2003; Brandt and Sdunowski 2007; Cheng et al. 2010). However, gas occurrence in most coal mines in China exhibits characteristics of low seepage pressure, low permeability, low saturability, and strong anisotropy (Yuan 2009; An et al. 2013; Jiang et al. 2013). There are many problems faced by attempting gas pre-drainage using existing technologies and large areas are therefore restricted for commercial development (Yuan 2009; Wang and Cheng 2012). In recent years, the technologies of protective seam mining of coal seam groups and gas drainage after pressure relief have become widely accepted in the coal industry, thereby realizing the scientific vision of gas drainage after pressure relief and the engineering practice of simultaneous coal and gas extraction (Cheng and Yu 2003; Cheng et al. 2004; Yu et al. 2004; Yuan 2010; Xie et al. 2014). With increasing of mining depth, all seams are upgraded to outburst coal seams (Wang et al. 2012b, 2013), which means that the first-mined seam (the protective seam) is hard to select and the elimination of outbursts in the entire region becomes difficult. The mining depth of many coal mines in the mid-east region of China has currently reached 800–1200 m, with vertical stress of 22–33 MPa, coal seam gas pressure and content of more than 6 MPa and 20 m3/t, respectively, and coal seam permeability of less than 0.001 mD—all of which make gas drainage even more difficult. An increase in permeability is the key measurement of effective and economic gas drainage in deep coal seams with low permeability (Chen et al. 2013; Guo and Cheng 2013; Xie et al. 2013; Pan et al. 2014).

Scholars from both home and abroad have conducted systematic research on the evolution of fracture development of overlying strata and the transport and accumulation characteristics of pressure-relief gas after mining, and have proposed, amongst others, the O-ring model (Qian and Xu 1998), the ring model of fracture in high-level positions (Yuan et al. 2011), the ‘∩’ top hat model (Yang and Xie 2008; Karacan and Goodman 2009), and the dynamic evolution of a fracture elliptic paraboloid zone of overlying mining strata (Li et al. 1999). These research achievements have provided some basis for establishing the theoretical and technical foundations for simultaneous extraction of coal and gas. However, the prior work placed particular emphasis on field experimentation and the analysis of the macroscopic phenomena of coal-rock mass damage and permeability change. Many permeability and theoretical studies have been carried out and many models proposed to explain the changes of permeability (Somerton et al. 1975; Harpalani and Mcpherson 1985; Palmer and Mansoori 1998; Robertson and Christiansen 2006; Li et al. 2007; Zhang et al. 2008; Connell et al. 2010; Liu et al. 2010a, b; Yin et al. 2011a, b). Most of these permeability models set gas extraction as the engineering background and assume that the coal stress–strain setting is that of uniaxial strain. The related experimental research is based on loading conditions and the unloading process cannot be described from a mechanical point of view (Xie et al. 2011b). There is little systematic study of the evolution of permeability under unloading conditions during the mining of coal and rock and only a few studies have examined the relationship between microscopic damage and permeability during loading (Xie et al. 2013). Based on the core concept of ‘mining-enhanced permeability’, this paper proposes a specific definition for the safe and efficient simultaneous extraction of coal and gas from deep coal seams. It establishes a theoretical model for coal unloading damage and permeability increasing. It also proposes ‘unloading by borehole drilling’ for single coal seams and ‘unloading by protective seam mining’ for groups of coal seams to realize the technical potential of simultaneous coal and gas extraction and its supporting drainage methods. In addition, the engineering applications of these principles in the Tunlan and the Panyi coal mines are described. These research results promote the safe and efficient simultaneous extraction of coal and gas from deep coal mines.

2 Definition of safe and efficient simultaneous extraction of coal and gas

Safe and efficient simultaneous extraction of coal and gas means that the two systems of coal exploitation and gas drainage are scientifically designed under a unified planning scheme. During coal exploitation, gas is efficiently extracted at the same time. Coal exploitation can provide the conditions for ‘mining-enhanced permeability’ and ‘space guarantee’ that are required for gas drainage. Gas drainage can transform outburst coal seams with high gas content into non-outburst seams with low gas content, thereby promoting the safe and efficient exploitation of coal (as shown in Fig. 1).

The traditional coal mining methods are as follows: Exploitation of a single seam starts from the shallow to the deep end, according to the mining level; for coal seam groups, exploitation takes place from the upper to the lower coal seams. Deep coal seams with high gas content show the characteristics of high ground stress, high gas pressure, and low permeability. Selection of the seam to be mined first is therefore very important. Generally, the seam which has the lowest gas content and little or no outburst risk is the perfect choice. As the mining depth increases, all coal seams become outburst-prone and there is no suitable seam to be mined first. In these cases, thin seams with high ash content or soft rock are chosen. To achieve mining-enhanced permeability, the mining height of the first-mined seam needs to reach a certain value. However, the higher the mining height of the first-mined seam, the more gangue will be produced from the working face, and the lower the economic benefit will be. We therefore need to choose the first-mined seam based on principles of both safety and economy. If the first-mined seam has coal and gas outburst risks, regional gas control methods should be used to eliminate this risk before mining.

The key to safe and efficient simultaneous extraction of coal and gas in deep coal seams is the integrated planning of the coal seam occurrence, the excavation system, gas control, and drainage engineering. For a single coal seam, we choose a region that has relatively good coal seam occurrence and low outburst risk as the first-mined zone and the gas is drained off the successive zones in advance. For coal seam groups, we choose a seam that has relatively low outburst risk, good pressure-relief effects, and is economical to mine as the first seam. Taking advantage of this mining approach, the adjacent coal seams experience pressure relief and the permeability will increase significantly, thereby providing efficient drainage conditions for pressure-relief gas, eliminating the outburst risk of adjacent seams, achieving effective coal exploitation, and realizing the safe and efficient extraction of coal and gas. The above ideas break with traditional thinking, which includes concepts such as ‘gas drainage accompanies coal exploitation with intense successive processes’, ‘mining from up to down’, and ‘choosing a non-outburst risk coal seam as the protective seam’. Using our approach, the entire coal mine and mineable seams can be planned uniformly and coal seam gas drainage can be optimally combined with safe and efficient coal exploitation.

3 Theoretical basis for safe and efficient simultaneous extraction of coal and gas

Guo et al. (2014) established a model of coal permeability based on the deformation of an effective matrix under the conditions of tri-axial stress. This formula includes effective stress and deformation of the coal matrix and it describes the influencing mechanisms of ground stress, pore pressure, and swelling deformation on the permeability of coal seam, concluding that the permeability of a coal seam is mainly controlled by ground stress and gas pressure. Combining the research on permeability in the Qinshui coal field and the statistics of field studies at an earlier stage, Meng et al. (2011) found that when the buried depth of the coal seam exceeds 700 m, ground stress becomes the dominant factor controlling the coal permeability. Cheng et al. (2013, 2014) concluded that ground stress in deep coal seam controls the change of effective stress, which also directly or indirectly influences the permeability (as shown in Fig. 2). Reducing the ground stress is therefore the only way to effectively increase coal permeability. When the external load decreases, coal swelling causes a decrease of pore pressure within the coal seam, which further increases the coal permeability. During the process of coal exploitation or gas drainage, the ground stress and gas pressure of adjacent coal seams decrease dramatically, which significantly changes the fracturing, thereby increasing the coal permeability.

Using the coupling property test of the adsorption–seepage mechanics of a coal-rock mass and a computer-aided tomography (CT) scanning system, we have systematically researched the fracture evolution and seepage characteristics of gas-containing coal during unloading (Fig. 3). We found that when the confining pressure reduces rapidly, coal permeability increases sharply. Coal experiences tension destruction during unloading, so new fractures connect with the original fractures, forming a fracture network (as shown in Fig. 4).

Using the experimental results for unloading and the trend of evolving permeability, combined with the current research findings, we established a conceptual model relating coal unloading damage to the evolution of permeability (Cheng et al. 2014), as shown in Fig. 5. This model describes the sharp increase of permeability during unloading (curve 3) as follows: during the initial stage, permeability increases slowly, along with a decrease of effective stress and the coal fractures partially recover, while the permeability is always less than that of the elastic model under the same conditions. When the effective stress decreases to a certain value, coal experiences unloading damage and new fractures are formed. The new fractures are distributed similarly to the old ones (Yu et al. 1998) and they contribute equally to permeability.

Based on an elastic-pore hypothesis and damage mechanics theory, combined with the relationship between unloading damage and permeability evolution for different unloading speeds and assuming that the volume of coal matrix is invariable, we established a theoretical model for unloading damage and permeability increase that starts from the unloading point G (Fig. 5) for conditions of volume expansion \((\varepsilon_{VG} - \varepsilon_{V} )\) and desorption swelling of the coal matrix \((\varepsilon_{mG} - \varepsilon_{m} )\) due to unloading tension (as shown in Eq. (1)). According to the distribution characteristics of the stress and strain of the first-mined seam and the adjacent seams during mining, we obtained the spatial and temporal distribution of permeability of unloading coal using this model (Cheng et al. 2014):

where ϕ and ε are porosity and strain, respectively, f m is an influential factor for desorption swelling of the coal matrix on the fracture strain, G in the subscript is the unloading point, m is the coal matrix, and V is volume.

4 Engineering methods for safe and efficient simultaneous extraction of coal and gas

4.1 Establishing a mining system for the safe and efficient simultaneous extraction of coal and gas from deep coal seams

The traditional view holds that underground mining of coal resources is the main task of production and that tunnels and gas control engineering are supporting systems. For working faces of coal seams with low gas contents, which have higher intensification, the designed production capacity can be achieved according to the pattern of ‘one coal mine, one mining area, and one working face’. Gas drainage is often an auxiliary system to prevent the gas concentration at the working face from exceeding a specified value. The mining mode is mainly by expansion from the central mining area to the boundary, from the shallow to the deep end, and the upper coal seam is often selected as the first-mined seam. For deep, outburst coal seams, regional gas drainage must be carried out before mining to eliminate the risks of coal and gas outbursts and to transform the outburst zones into non-outburst zones. Only then can the excavation proceed. Investigation of the causes of a large number of serious and major gas disasters in coal mines indicates that the imbalance between ‘drainage, excavation, and mining’ is one of the important reasons for gas accidents. Integrated planning of the entire mineable seam area of coal mines is therefore needed. In addition, gas drainage technology for outburst coal seams and those with high gas content needs demonstration of feasibility and optimization. The amount of gas drainage required and its schedule of removal in the project also need to be estimated in advance. On the basis of the above, we have formulated a plan for coal mining and gas drainage to ensure a balance between ‘drainage, excavation, and mining’, and thereby provide conditions for ‘mining-enhanced permeability’ and ‘space guarantee’ for gas drainage.

For single outburst coal seams, a penetration or bedding borehole is usually adopted for regional gas drainage that requires a long drainage time. To guarantee the regular succession of working faces, the production layout should be at least one double wing or two single wing areas, ensuring that the mine has a layout comprising a ‘planning area, preparation area, and production area’ (Wang et al. 2008). This then forms the virtuous cycle of ‘one mining, one drainage, one preparation’, and ensures safe and efficient simultaneous extraction of coal and gas.

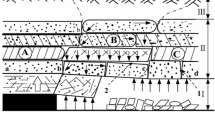

For coal seam groups, simultaneous extraction of coal and gas means breaking the traditional mining sequence, and we select the first-mined seam according to the principles of safety and economy. If the first-mined seam has a risk of coal and gas outbursts, then this risk should be eliminated using a similar regional gas-drainage method for a single outburst coal seam. Exploitation of the first-mined seam will generate ‘mining-enhanced permeability and gas flow ability’ in the coal strata, and activate flow conditions for the ‘desorption–diffusion–seepage’ of gas. Combining a reasonable and efficient gas-drainage method and system can enable efficient gas drainage to be simultaneously realized. During exploitation of the first-mined seam, the adjacent upper and lower protected seams all need supporting systems for gas drainage. In addition to the production system for the first-mined seam, the production systems and necessary gas-drainage roadways should also be arranged in advance in the upper and lower adjacent coal seams, and gas-drainage boreholes constructed to extract pressure-relief gas promptly and effectively. By collaborative mining of the first-mined seam and the adjacent protected seams, the layout of ‘one mining face, one drainage face, and one preparation face’ can be achieved. To realize complete and sufficient pressure relief of protected adjacent coal seams, the working face of the first-mined seam should advance the protected seam working face by one to two sections in the tilt direction and must ensure sufficient advance time. For full protection of the protected coal seams at the same level, the mining range of the protective seam must be expanded in the tilt direction and the lower limit of mining of the protective seam extended along the tilt direction (as shown in Fig. 6). Apart from normal mining levels, auxiliary levels also need to be established to mine the subjacent part of the protective seam. To ensure continuous mining of the subjacent part of the protective seam, horizontal alleys have to be arranged in the floor strata of the protective seam to avoid being damaged. The parameters of the subjacent part of the protective seam mining of each mine in the Sunan mining area of the Huaibei coalfield are shown in Table 1.

It can be seen that the construction of spatial and gas systems for simultaneous extraction of coal and gas are based on the principle of balance between ‘drainage, excavation, and mining’. Medium- and long-term planning of coal mine gas drainage can ensure the ‘time–space’ conditions for gas drainage, achieve a match between coal mining quantity and the safe coal quantity after effective gas drainage, and maintain mining production activities in the safe coal quantity area.

4.2 Construction of gas drainage systems in safe and efficient simultaneous extraction of coal and gas from deep coal seams

According to the model and combining the single and group coal seam characteristics, we propose the reservoir joint transformation method for unloading the first-mined coal seam by borehole drilling and unloading adjacent seams by protective seam mining, constructing a gas-guiding channel combined with a preset screen pipe, pressure-relief borehole, and surface well drilling, to achieve an integrated design and spatial extraction of gas control in deep coal seam groups with high gas content.

4.2.1 Permeability enhancement of the first-mined coal seam and optimum construction method for the gas channel

Bedding or penetration boreholes are adopted for regional gas pre-drainage of the first-mined seam. During the drilling process, gassy coal with low intensity can discharge a large amount of pulverized coal (1.3–1.5 times the volume of the borehole). The volume of discharged pulverized coal can reach from twice to 30 times the volume of the borehole in the developed area. The coal mass continues to experience flowing deformation to the borehole under the influence of in situ stress. Under certain borehole densities, unloading in a large area can be achieved (Zhou et al. 2012), as shown in Fig. 7. According to the model, the permeability of the first-mined seam relates positively to borehole density. When the buried depth exceeds 800 m, the length of borehole per ton must be 0.3–0.5 m and borehole spacing less than 3.0 m (aperture is 100 mm) to ensure gas drainage from the first-mined seam). In this case, the inter-hole vertical stress decreases by 10 % and the coal permeability increases by almost 20 times.

After drilling, the surrounding coal mass flows to the borehole and this can increase the permeability, but can also clog the flow channel. By presetting the screen of the borehole, we can build an artificial gas flow channel (Fig. 8). To maintain a negative drainage pressure and the gas concentration, we seal the borehole by blocking both ends and grout twice under pressure at two places so that the broken rock zone of the drilling roadway can be sealed. After implementing the preset screen in the Huainan and Huaibei mining areas, the rate of formation of drilling boreholes exceeded 95 %. When the sealing length is 15–20 m and the negative pressure is 15–20 kPa, the initial gas drainage concentration can reach 60 %–80 %. This reduces to 10 %–20 % after 3 months, demonstrating the effectiveness of constructing this gas channel for the first-mined seam. Hydraulic measures can increase the effect of coal unloading, so the spacing of drilling boreholes can be increased appropriately when they were adopted.

4.2.2 Permeability enhancement of the adjacent seams and optimum construction method for the gas channel

In the process of exploiting the first-mined seam, the upper and lower adjacent seams experience the sequential phenomena of stress concentration, unloading damage, and stress recovery (Liu et al. 2011, 2012), while the coal experiences the deformational characteristics of compression, expansion, and recompression. The stress and deformation fields of adjacent seams were obtained by numerical simulation. We applied the model to obtain spatial and temporal distributions of permeability of the adjacent seams. These experience four stages, namely a decrease, followed by an increase, then stabilization and attenuation (Fig. 9).

Interlayer spacing has a significant influence on the permeability of adjacent seams. For example, if the upper adjacent seam is located at a position 20 times the mining height, the vertical stress decreases by nearly 60 %, the expansive deformation rate is about 60 %, and permeability increases about 3000 times. When the upper adjacent seam is located at a position 40 times of the mining height, vertical stress decreases by nearly 35 %, the expansive deformation rate is about 10 %, and permeability increases about 1000 times (Fig. 10a). The permeability of an adjacent seam that is 20 m below the first-mined seam increases over 1000 times. However, when the interlayer spacing expands to 50 m, the permeability only increases about 300 times (Fig. 10b). Affected by the first-mined seam, the adjacent seam experiences unloading, expansion, fracture development, and then forms a gas flow channel. Some of the drainage boreholes, such as surface and penetration boreholes, can be used to establish an artificial flow channel for pressure-relief gas and to drain this gas efficiently during the periods of permeability increase and stabilization (Zhou et al. 2012). Using theoretical calculations and engineering practices, we quantified the layout parameters for drainage boreholes under different conditions in a mining area. It is generally believed that for areas in which the permeability of an adjacent seam increases by more than 2000 times, the borehole spacing should be 20–40 m; for areas in which the permeability increases between 1000 and 2000 times, the borehole spacing should be 10–20 m; and where the permeability increases between 300 and 1000 times, the borehole spacing should be 5–10 m. The drainage boreholes of adjacent seams should be constructed and interconnected for drainage, and should also be 200 m ahead of the working face of the first-mined seam.

4.3 Methods for spatial and comprehensive gas drainage

After the first-mined seam and adjacent seam are determined, the equivalent relative interlayer spacing (Liu et al. 2010b) can be calculated according to the occurrence of the coal strata, mining parameters for the working face, and interlayer lithology coefficient. The gas emissions from the gob of the working face are then divided into short-, medium-, and long-distance gas emissions, according to the relative spacing of the layers. Short-distance gas emissions mainly come from unexploited parts of first-mined seam, residual coal from the gob, coal seams in the caving zone, the heaving deformation zone in the bottom seam, and part of the fault zone; medium-distance gas emissions predominantly originate from the fault zone and part of the bending zone; while long-distance gas emissions come mainly from the bending zone. The conditions for ‘desorption, diffusion, and seepage’ differ for emissions from these different distances. The different gas emission and migration patterns require different methods of gas drainage. The methods of gas drainage from the first-mined seam and adjacent seam are shown in Table 2.

5 Engineering applications of safe and efficient simultaneous extraction of coal and gas

5.1 Engineering of the Panyi coal mine in Anhui Province

The coal strata of the Huainan mining area belong to the Carboniferous–Permian category with multiple coal seams, which can be divided into three groups (A, B, and C) from the bottom to the top. The B and C groups are the main coal mining groups, with 10 to 19 mineable seams. The total thickness of the mineable seams is 23–36 m, so the coal resources are abundant. With the increasing of mining depth, the gas pressure and content of each main coal mining seam increases year on year and the risk of coal seam outbursts escalates. Most of the current mining seams have been upgraded to outburst seams. Gas control of these outburst seams has become the primary problem that needs to be solved in this area. With the typical occurrence of coal seams, protective seam mining is used. Every coal mine has 13–16 coal seams, including the main mining seams, C13, B11b, B10, B8, B6, B4b, and A1, all of which are outburst seams. The thickness of the B10 seam is 0–1.85 m with an average of 0.9 m, and its outburst risk is relatively low compared with that of other seams. The distance between the B10 and upper B11b coal seams is 30 m and the spacing to the lower B8 seam is 40 m, as shown in Fig. 11a.

By comparing and analyzing each coal seam, B10 was chosen as the key protective seam to be mined first. As a result of the movement and deformation of the roof and floor strata after mining, the upper protected seams B11 and B8 gained mining-enhanced permeability. Combining the pressure-relief gas-drainage technology of the protected seams, the B11 and B8 seams in the roof and floor were transformed from high gassy coal seams with outburst risks to low gassy coal seams without outburst risks. The C13 seam is located in the upper layer of B11. To control the gas from C13, the B11 seam (in which the outburst risk has been eliminated) is chosen as the second protective seam to mine, enabling the C13 seam to gain the effect of unloading and enhanced permeability, and thereby eliminate its outburst risk by combination with the pressure-relief gas-drainage technology. There are many coal seams in the lower part of the B8 seam. To eliminate the outburst risk of each seam, mining from top to bottom and layer by layer is needed. The upper seam can also protect the lower seam. Combined with pressure-relief gas drainage technology, mining of the upper seam allows the lower seam to gain the effect of unloading and enhanced permeability, which eventually eliminates the outburst risk, as shown in Fig. 11b. After eliminating the outburst risk, the B8 seam is regarded as the sub-1 protective seam to protect the lower B7a seam. Then the B7a seam is the sub-2 protective seam to protect the lower B6 seam, the B6 seam is the sub-3 protective seam to protect the lower B4 seam, the B4 seam is the sub-4 protective seam to protect the lower A3 seam, and the A3 seam is the sub-5 protective seam to protect the lower A1 seam. Each seam adopts protective seam mining technology and eliminates the risk of outbursts.

Due to the sequence of mining from top to bottom and the small interlayer spacing, the lower coal seams can benefit many times from the unloading effects. The Panyi coal mine in Huainan adopted the mode of ‘key protective layer mining with grouping and spatial gas drainage’ to realize joint unloading reconstruction of the upper and lower adjacent seams (Cheng et al. 2004; Wang 2011; Wang et al. 2012c). After mining of protective seam B11, the maximum expansive deformation of the coal seam C13 was 26.3 % and its permeability coefficient increased 2880 times. The gas drainage rate of C13 exceeded 60 %, the gas content of the coal seam declined effectively from 13 to 5.2 m3/t, and gas pressure dropped from 4.4 to 0.4 MPa, which indicated that the outburst risk of this coal seam had been completely eliminated. The practice of mining the protected seam enabled the monthly tunneling speed of the coal roadway to increase from the original of 40–60 m to more than 200 m per month. Combined with a comprehensive mechanization caving coal mining method, the working face can achieve production capacity of 10000 t/d.

5.2 Engineering of the Tunlan coal mine in Shanxi Province

The Tunlan coal mine is located in the middle of the Xishan coalfield, which is one of the six major coalfields in Shanxi. This mine is also situated in the southwest of Taiyuan, Shanxi Province, at the northern rim of the Qinshui Basin. The mine was formally put into production in 2002 with a design capacity of 4 million t/a. The main coal-bearing strata are the Taiyuan Formation of the Upper Carboniferous System and the Shanxi Formation of the lower Permian Period. The occurrence is relatively stable, and the mineable seams are the No. 2 and No. 4 seams of the Shanxi Formation and the No. 7, No. 8, and No. 9 seams of the Taiyuan Formation. There are many mineable seams with short distances, which have the characteristics of short-distance coal seam groups. With increasing service life of the mine and increasing mining depth, the possibility of gas disasters became increasingly serious. According to a gas grade appraisal in 2012, the absolute gas emission quantity was 223 m3/min and the relative gas emission rate was 39.71 m3/t. On February 22, 2009, due to insufficient gas drainage and an unreliable ventilation system, local gas accumulation occurred. This caused an extremely serious gas explosion with 78 fatalities and 114 injuries, which received widespread attention from the industry. By combining theoretical analysis and field engineering practice, the technology models for this high gas coal seam group reservoir were constructed and ground and underground wells for spatial gas drainage were proposed (Kong et al. 2014). Surface wells were used to drain the gas from the first-mined seam, which has a high gas content and good economics, and thereby eliminate the outburst risk of the first-mined seams (as shown in Fig. 12). Taking advantage of the mining method, we reconstructed the remaining adjacent coal seams. Ground and underground wells for spatial gas drainage were also adopted to efficiently drain the pressure-relief gas from the adjacent seams, eliminating the outburst risks of these seams, and eventually achieving safe and efficient mining of the entire coal seam group.

This method provides a new concept for achieving efficient simultaneous exploitation of coal and gas at deep environments and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Industrial tests were carried out separately in the Tunlan coal mine using the key technologies of this model. The model has now been integrated into commercial technology and has already achieved good results. After completing construction of the surface-fracturing wells, the gas-drainage volumes were relatively stable (the average concentration exceeded 80 %) and the average flow of pure gas is about 619 m3/d. The highest average pure gas from the underground bedding borehole can amount to 7 m3/min and the average drainage gas flow is 3.39 m3/min. A tunnel was constructed in the adjacent coal seam under the first-mined working face and the bedding borehole was then constructed on both sides to cover the projection area of this face. Because of mining of the first-mined seam, the desorption flow of gas in the coal body was greatly accelerated. The quantity of pure gas drainage was therefore relatively high, with an average of 5.79 m3/min.

6 Conclusions

This paper proposed a definition for the safe and efficient extraction of coal and gas. Guided by a unified planning scheme, we scientifically designed two systems for coal exploitation and gas drainage, which allow gas drainage to be effectively carried out during the production of coal. Coal exploitation can provide the required conditions of ‘mining-enhanced permeability’ and ‘space guarantee’ for gas drainage. Gas drainage can transform outburst-prone coal seams with high gas content into non-outburst coal seams with low gas content. This concept enables the entire coal mine and mineable seams to be planned uniformly and coal seam gas drainage can be optimally combined with safe and efficient coal exploitation.

Ground stress in deep coal seams controls the change of effective stress: reducing ground stress is the only effective way to increase permeability of coal. Through a laboratory and theoretical study, this paper establishes a theoretical model of unloading damage and permeability enhancement. This model also links the concepts of stress and seepage, making gas-drainage design more scientific and effective.

Methods are proposed for enhancing permeability of the first-mined and adjacent seams and constructing a gas tunnel. We determine the first-mined seam according to principles of safety and economy. The first-mined seam is then transformed by borehole drilling to increase its permeability. Coal seam gas can then be drained and its outburst risk eliminated. Mining of the first-mined seam can transform the adjacent seams and improve their permeability and drainage. Drainage is accomplished by a gas flow tunnel through a preset screen pipe and pressure-relief and surface boreholes. The model allows quantification indexes of the drainage boreholes of the first and adjacent seams, which can satisfy the criteria for mining-enhanced permeability. Finally, the goal of integrated design and spatial gas drainage from deep coal seam groups with high gas contents is realized.

These methods have been successfully applied in the Panyi and Tunlan coal mines, where ‘surface–underground’ spatial gas-drainage patterns were established, thereby promoting the safe and efficient extraction of coal and gas from outburst coal mines. In addition, most coal mines with high gas content in China exhibit the characteristics of coal seam groups, which presents prospects for wide application of this system.

References

An FH, Cheng YP, Wu DM, Wang L (2013) The effect of small micropores on methane adsorption of coals from northern China. Adsorption 19(1):83–90

Authorized Committee of Coal Science and Technology Term (1996) Coal science and technology term. Science Press, Beijing

Brandt J, Sdunowski R (2007) Gas drainage in high efficiency workings in German Coal mines. In: Proceeding of 2007 China (Huainan) International Symposium on Coal gas control technology. Xuzhou, China University of Mining and Technology Press:22–29

Chen HD, Cheng YP, Zhou HX, Li W (2013) Damage and permeability development in coal during unloading. Rock Mech Rock Eng 46(6):1137–1390

Cheng YP, Yu QX (2003) Safe and efficient simultaneous extraction system of coal and gas and application on coal seam group. J China Univ Min Technol 32(5):471–475

Cheng YP, Yu QX, Yuan L, Li P, Liu YQ, Tong YF (2004) Experimental research of safe and high-efficient exploitation of coal and pressure relief gas in long distance. J China Univ Min Technol 33(2):132–136

Cheng YP, Wang HF, Wang L, Zhou HX, Liu HY, Liu HB, Wu DM, Li W (2010) Theories and engineering applications on coal mine gas control. China University of Mining and Technology Press, Xuzhou

Cheng YP, Wang L, Zhang XL (2011) Environmental impact of coal mine methane emissions and responding strategies in China. Int J Greenhouse Gas Control 5(1):157–166

Cheng YP, Zhang XL, Wang L (2013) Controlling effect of ground stress on gas pressure and outburst disaster. J Min Saf Eng 30(3):408–414

Cheng YP, Liu HY, Guo PK, Pan RK, Wang L (2014) A theoretical model and evolution characteristic of mining-enhanced permeability in deeper gassy coal seam. J China Coal Soc 39(8):1650–1658

Connell LD, Lu M, Pan Z (2010) An analytical coal permeability model for tri-axial strain and stress conditions. Int J Coal Geol 84(2):103–114

Creedy D, Tilley H (2003) Coal-bed methane extraction and utilization. J Power Energy 217:19–25

Flores RM (1998) Coalbed methane: from hazard to resource. Int J Coal Geol 35:3–26

Guo PK, Cheng YP (2013) Permeability prediction in deep coal seam: a case study on the no. 3 coal seam of the southern Qinshui Basin in China. Sci World J. doi:10.1155/2013/161457

Guo PK, Cheng YP, Jin K, Li W, Tu QY, Liu HY (2014) Impact of effective stress and matrix deformation on the coal fracture permeability. Transp Porous Media 103(1):99–115

Harpalani S, Mcpherson M (1985) Effect of stress on permeability of coal. Q Rev Methane Coal Seams Technol 3(2):23–28

IPCC (2007) Climate change 2007: synthesis report. Contribution of working groups I, II and III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Geneva, Switzerland

Jiang HN, Cheng YP, Yuan L, An FH, Jin K (2013) A fractal theory based fractional diffusion model used for the fast desorption process of methane in coal. Chaos 23(3):033111

Karacan CÖ, Goodman G (2009) Hydraulic conductivity changes and influencing factors in longwall overburden determined by slug tests in gob gas vent holes. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 46:1162–1174

Kong S, Cheng Y, Ren T, Liu HY (2014) A sequential approach to control gas for the extraction of multi-gassy coal seams from traditional gas well drainage to mining-induced stress relief. Appl Energy 131:67–78

Li SG, Shi PW, Qian MG (1999) Study on the dynamic distribution features of mining fissure elliptic paraboloid zone. Ground Press Strat Control 3–4:44–46

Li XC, Guo YY, Wu SY, Nie BS (2007) Mathematical model and numerical simulation of fluid-solid coupled flow of coal-bed gas considering swelling stress of adsorption. Chin J Rock Mech Eng 26(z1):2743–2748

Liu HY, Cheng YP, Zhao CC, Zhou HX, Zhang ZP (2010a) Classification and judgment method of the protective layers. J Min Saf Eng 27(4):468–474

Liu JS, Chen ZW, Elsworth D, Xie XM, Xian BM (2010b) Linking gas-sorption induced changes in coal permeability to directional strains through a modulus reduction ratio. Int J Coal Geol 83(1):21–30

Liu HY, Cheng YP, Chen HD, Kong SL, Xu C (2011) Characteristics of depressurized fissure and its effect on deformation induced pressure relief of mining coal mass containing gas. J China Coal Soc 36(12):2074–2079

Liu HY, Cheng YP, Chen HD, Kong SL, Xu C (2012) Characteristics of mining gas channel and gas flow properties of overlying stratum in high intensity mining. J China Coal Soc 37(9):1437–1443

Meng ZP, Zhang JC, Wang R (2011) In-situ stress, pore pressure and stress-dependent permeability in the southern Qinshui Basin. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 48(1):122–131

National Bureau of Statistics of People’s Republic of China. Statistical Bulletin of National Economy and Social Development in 2013 (2014)

Noack K (1998) Control of gas emissions in underground coal mines. Int J Coal Geol 35:57–83

Palmer I, Mansoori J (1998) How permeability depends on stress and pore pressure in coalbeds: a new model. SPE Reserv Eval Eng 1:539–544

Pan RK, Cheng YP, Yuan L, Yu MG, Dong J (2014) Effect of bedding structural diversity of coal on permeability evolution and gas disasters control with coal mining. Nat Hazards 73(2):531–546

Qian MG, Xu JL (1998) Study on the “O-shape” circle distribution characteristics of mining-induced fractures in the overlaying strata. J China Coal Soc 23(5):466–469

Robertson EP, Christiansen RL (2006) A permeability model for coal and other fractured, sorptive-elastic media. Idaho National Laboratory, INL/EXT-06-11830

Somerton WH, Söylemezoḡlu I, Dudley R (1975) Effect of stress on permeability of coal. Proc Int J Rock Mech Min Sci Geomech Abstr 12:129–145

Wang JC (2011) Keytheoretical issue need to be solved and research status of coal and gas co-mining. Coal Eng 1:1–3

Wang L, Cheng YP (2012) Drainage and utilization of Chinese coal mine methane with a coal–methane co-exploitation model: analysis and projections. Resour Policy 37:315–321

Wang HF, Cheng YP, Yu QX, Zhou ZY, Zhou HX, Liu HY (2008) Research on the amount of safely mineable coal in mines susceptible to coal and gas outburst. J China Univ Min Technol 37(2):236–240

Wang L, Cheng YP, Liu HY (2012a) An analysis of fatal gas accidents in Chinese coal mines. Saf Sci 62:107–113

Wang L, Cheng YP, Wang L, Guo PK, Li W (2012b) Safety line method for the prediction of deep coal-seam gas pressure and its application in coal mines. Saf Sci 50(3):523–529

Wang HF, Cheng YP, Wang L (2012c) Regional gas drainage techniques in Chinese coal mines. Int J Min Sci Technol 22(6):873–878

Wang HF, Cheng YP, Yuan L (2013) Gas outburst disasters and the mining technology of key protective seam in coal seam group in the Huainan coalfield. Nat Hazards 67(2):763–782

Wang L, Cheng YP, An FH, Zhou HX, Kong SL, Wang W (2014) Characteristics of gas disaster in the Huaibei coalfield and its control and development technologies. Nat Hazards 71:85–107

Xie HP, Qian MG, Peng SP, Hu XS, Peng YQ, Zhou HW (2011a) Preliminary exploitation on coal science production and development strategy. China Eng Sci 13(6):44–50

Xie HP, Zhou HW, Liu JF, Gao F, Zhang R, Xue DJ, Zhang Y (2011b) Mining-induced mechanical behavior in coal seams under different mining layouts. J China Coal Soc 36(7):1067–1074

Xie HP, Gao F, Zhou HW, Cheng HM, Zhou FB (2013) On theoretical and modeling approach to mining-enhanced permeability for simultaneous exploitation of coal and gas. J China Coal Soc 38(7):1101–1108

Xie HP, Zhou HW, Xue DJ, Gao F (2014) Theory, technology and engineering of simultaneous exploitation of coal and gas in China. J China Coal Soc 39(8):1391–1397

Yang K, Xie GX (2008) Caving thickness effects on distribution and evolution characteristics of mining induced fracture. J China Coal Soc 33(10):1092–1096

Yin GZ, Jiang CB, Xu J, Peng SJ, Li WP (2011a) Experimental study of thermo-fluid-solid coupling seepage of coal containing gas. J China Coal Soc 36(9):1495–1500

Yin GZ, Jiang CB, Wang WZ, Huang QX, Si HR (2011b) Experimental study of influence of confining pressure unloading speed on mechanical properties and gas permeability of containing-gas coal rock. Chin J Rock Mech Eng 30(1):68–77

Yu GM, Xie HP, Zhou HW, Zhang YZ, Yang L (1998) Distribution law of cracks in structured rock mass and its experimental investigation. J Exp Mech 13(2):14–23

Yu QX, Cheng YP, Jiang CL, Zhou SN (2004) Principles and applications of exploitation of coal and pressure relief gas in thick and high-gas seams. J China Univ Min Technol 33(2):127–131

Yuan L (2009) Theory of pressure-relieved gas extraction and technique system of integrated coal production and gas extraction. J China Coal Soc 34(1):1–8

Yuan L (2010) Concept of gas control and simultaneous extraction of coal and gas. China Coal 6:5–12

Yuan J, Naruse I (1999) Effects of air dilution on highly preheated air combustion in a regenerative furnace. Energy Fuels 13:99–104

Yuan L, Guo H, Shen BT, Qu QD, Xue JH (2011) Circular overlying zone at long wall panel for efficient methane capture of multiple coal seams with low permeability. J China Coal Soc 36(3):357–365

Yuan L, Qin Y, Cheng YP (2012) Research on strategic of CBM exploration and development in China. China Engineering Academy, Beijing

Zhang HB, Liu JS, Elsworth D (2008) How sorption-induced matrix deformation affects gas flow in coal seams: a new FE model. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 45(8):1226–1236

Zhou HX, Wang L, Cheng YP, Wang LG (2012) Guide channel construction for gas drainage and its application in coal seams with low permeability and strong burst-proneness. J China Coal Soc 37(9):1456–1460

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Program on Key Basic Research Project of China (973 Program) (2011CB201204), the Visitor Foundation of the State Key Laboratory of Coal Mine Disaster Dynamics and Control (Chongqing University) (2011DA105287–FW201405), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51374204 and 51304204), and a project funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Cheng, Y., Wang, L., Liu, H. et al. Definition, theory, methods, and applications of the safe and efficient simultaneous extraction of coal and gas. Int J Coal Sci Technol 2, 52–65 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40789-015-0062-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40789-015-0062-5